Fundamentals

That persistent feeling of being simultaneously exhausted and agitated, the afternoon energy slumps that send you searching for sugar, and the sense that your body is running on a depleting battery are common experiences. These sensations are not just in your head; they are biological signals.

Your body is communicating a disruption in a deeply intelligent system designed to manage stress and energy. This system, the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis, functions as the command center for your stress response. When it is functioning optimally, it orchestrates a graceful rhythm of hormones that helps you wake up with vigor, navigate daily challenges, and wind down for restorative sleep.

At the heart of this system is cortisol, a hormone that does much more than simply react to stress. It follows a natural, daily pattern, peaking in the morning to promote alertness and gradually declining throughout the day to allow for sleep.

However, modern life ∞ with its relentless pace, poor sleep patterns, and processed diets ∞ can disrupt this rhythm. Chronic activation of the stress response keeps cortisol levels elevated when they should be low, or flattens the curve, leaving you feeling drained. This state of HPA axis dysregulation creates a cascade of metabolic consequences.

Your body’s ability to manage blood sugar becomes impaired, leading to cravings, weight gain around the midsection, and a cycle of energy spikes and crashes. The communication between your adrenal system and your metabolic system becomes confused, and the symptoms you feel are the direct result of this internal miscommunication.

Nutritional strategy provides the raw materials to re-establish clear communication between your body’s stress-response and energy-management systems.

The path to re-establishing balance begins with understanding that your food choices are powerful modulators of this system. The goal is to use nutrition to stabilize blood sugar and provide the necessary building blocks for healthy hormone production. This process starts with recognizing the profound impact of macronutrients ∞ protein, fat, and carbohydrates ∞ on this delicate hormonal conversation.

Each meal is an opportunity to send a signal of safety and stability to the HPA axis, helping it to recalibrate and restore its natural, life-sustaining rhythm.

The Central Role of Blood Sugar Stability

The relationship between cortisol and insulin, your primary blood sugar-regulating hormone, is deeply intertwined. When you consume high-sugar or refined carbohydrate foods, your blood glucose spikes rapidly. The body responds by releasing a surge of insulin to shuttle that glucose into your cells for energy.

This rapid rise and fall of blood sugar is itself a physiological stressor, prompting the HPA axis to release cortisol to prevent blood sugar from dropping too low. This creates a volatile cycle ∞ high cortisol can contribute to insulin resistance, where your cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals, leading to higher blood sugar levels and more fat storage. In turn, unstable blood sugar triggers more cortisol release.

A foundational nutritional strategy is to slow down the absorption of glucose into the bloodstream. This is achieved by ensuring every meal and snack is balanced. Combining complex carbohydrates (like sweet potatoes or quinoa) with high-quality protein (like chicken, fish, or legumes) and healthy fats (like avocado or olive oil) prevents the sharp spikes and subsequent crashes in blood sugar.

Protein and fat slow down digestion, promoting a more gradual release of glucose. This simple act of food combination sends a calming signal to the HPA axis, reducing the need for emergency cortisol production and allowing the system to return to a state of equilibrium.

Building Blocks for Hormonal Communication

Your body cannot create hormones out of thin air. It requires specific nutritional cofactors to synthesize and regulate the very molecules that govern your energy and stress response. The adrenal glands, in particular, have a high demand for certain vitamins and minerals to function correctly. Chronic stress depletes these essential nutrients, further impairing the body’s ability to manage the HPA axis.

Key nutrients serve as the foundational support for this system. Vitamin C is found in very high concentrations in the adrenal glands and is essential for cortisol production and regulation. B vitamins, especially B5 (pantothenic acid), are critical for adrenal function and energy metabolism.

Magnesium is another vital mineral that has a calming effect on the nervous system and helps regulate the HPA axis; a deficiency can exacerbate the stress response. By focusing on a diet rich in whole, unprocessed foods ∞ such as leafy greens, colorful vegetables, citrus fruits, nuts, and seeds ∞ you provide a steady supply of these crucial micronutrients.

This dietary approach ensures that the adrenal glands are well-equipped to perform their duties without becoming depleted, supporting the entire hormonal cascade from the top down.

Intermediate

Moving beyond foundational principles, a more sophisticated approach to nutritional support for adrenal-metabolic balance involves targeted strategies that align with the body’s natural biological rhythms. This means looking at not only what you eat, but also when and how you eat, to more precisely modulate the HPA axis and improve metabolic flexibility.

The conversation shifts from merely preventing blood sugar crashes to strategically using nutrients to reinforce the body’s innate circadian clock, a central regulator of both cortisol and metabolic function. This level of intervention recognizes that the body’s needs change throughout the day and that aligning nutritional intake with these changes can profoundly enhance systemic balance.

This intermediate strategy also delves into the world of specific bioactive compounds found in foods and herbs. These are not just basic vitamins and minerals, but potent phytochemicals and fatty acids that can directly influence inflammatory pathways, support neurotransmitter production, and enhance cellular resilience to stress.

By incorporating these elements, you are providing a higher level of information to your biological systems, helping to quiet the noise of chronic stress and restore more efficient function. The focus becomes one of active recalibration, using food as a daily tool to fine-tune the intricate dialogue between the adrenal, metabolic, and nervous systems.

What Is the Best Way to Time Nutrient Intake?

The concept of nutrient timing is based on the understanding that our bodies are primed to handle different macronutrients more effectively at different times of the day, largely due to the natural rhythm of cortisol. Cortisol is typically highest in the morning, which promotes alertness and mobilizes energy.

A high-protein breakfast can leverage this state by providing the building blocks for neurotransmitters and promoting stable blood sugar throughout the day. Consuming the majority of complex carbohydrates in the evening, on the other hand, can support the production of serotonin, a neurotransmitter that is a precursor to melatonin, the sleep hormone. This can help to lower cortisol levels at night, facilitating restorative sleep and reinforcing a healthy circadian rhythm.

This approach contrasts with the common practice of consuming carb-heavy breakfasts and light, salad-based dinners. By front-loading protein and saving the bulk of your complex carbohydrates for the evening meal, you work with your body’s hormonal flow. This strategy can improve insulin sensitivity over time and help restore a more robust cortisol curve, leading to better energy during the day and more restful sleep at night.

Aligning carbohydrate intake with the body’s natural cortisol decline in the evening can significantly improve sleep quality and metabolic signaling.

A practical application involves structuring meals to support this rhythm. A morning meal might consist of eggs and avocado, while an evening meal could include baked salmon with a sweet potato and steamed broccoli. This temporal arrangement of macronutrients is a powerful tool for reinforcing the body’s natural cycles, which are often disrupted by chronic stress and erratic eating habits.

Targeted Micronutrients and Adaptogenic Support

While a whole-foods diet provides a broad spectrum of nutrients, certain clinical situations involving HPA axis dysregulation may benefit from a focus on specific micronutrients and botanical compounds. These agents offer a more targeted level of support, addressing the biochemical consequences of chronic stress.

- Magnesium ∞ This mineral is crucial for nervous system regulation and is rapidly depleted during periods of stress. Magnesium supplementation, particularly in forms like magnesium glycinate, can help to calm the HPA axis by modulating the activity of the pituitary gland and reducing the release of stress hormones.

- Omega-3 Fatty Acids ∞ Found in fatty fish like salmon and sardines, as well as in flax and chia seeds, these fats are potent anti-inflammatory agents. Chronic stress promotes inflammation, which can further dysregulate the HPA axis. Omega-3s help to quell this inflammation and have been shown to support healthy cortisol levels.

- Adaptogenic Herbs ∞ Adaptogens are a class of herbs that may help the body adapt to and resist the negative effects of stress. Plants like Ashwagandha and Rhodiola rosea have been studied for their potential to modulate cortisol production and improve the body’s resilience to stress. It is important to approach adaptogens with care, as their effects can be potent and quality varies widely. Their use is best guided by a knowledgeable practitioner.

These targeted interventions should be viewed as complements to, not replacements for, a sound foundational diet. They provide an additional layer of support to help restore balance when the system is significantly depleted.

| Dietary Approach | Primary Mechanism | Key Foods | Primary Benefit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean Diet | Reduces inflammation and oxidative stress through high intake of healthy fats and antioxidants. | Olive oil, fatty fish, nuts, seeds, fruits, vegetables, legumes. | Broad-spectrum cardiovascular and metabolic protection. |

| Low-Glycemic Diet | Minimizes blood sugar and insulin spikes by focusing on low-glycemic index carbohydrates. | Non-starchy vegetables, legumes, whole grains, lean proteins. | Directly supports blood sugar stability and reduces stress on the HPA axis. |

| Nutrient Timing Model | Aligns macronutrient intake with the body’s natural circadian and cortisol rhythms. | Protein-rich breakfast, complex carbohydrates in the evening. | Reinforces healthy sleep-wake cycles and improves metabolic flexibility. |

Academic

An academic exploration of nutritional strategies for adrenal-metabolic health requires a shift in perspective toward the molecular and systemic interactions that govern homeostasis. The focus moves from macronutrient composition to the intricate signaling pathways that are influenced by dietary inputs.

At this level, we examine how specific food-derived molecules interact with cellular receptors, modulate gene expression, and influence the complex, bidirectional communication network that links the central nervous system, the endocrine system, and the gut microbiome. This systems-biology approach recognizes that HPA axis dysregulation is not an isolated glandular issue but a reflection of systemic imbalance, often rooted in chronic low-grade inflammation and cellular stress.

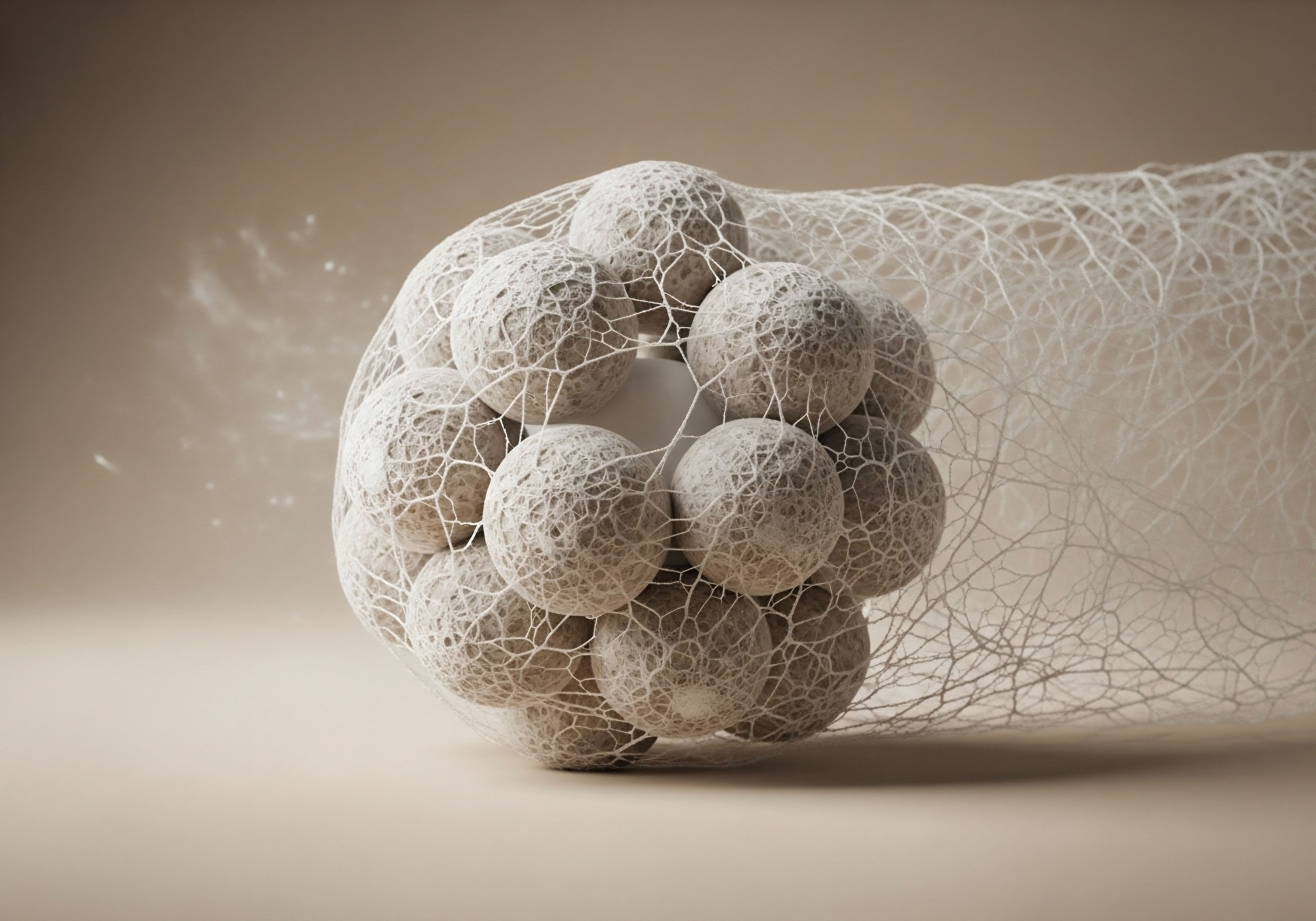

The central thesis of this advanced perspective is that nutrition provides a powerful set of tools to modulate the gut-brain-adrenal axis. The gut microbiome has emerged as a critical endocrine organ in its own right, capable of producing neurotransmitters, metabolizing hormones, and regulating systemic inflammation.

Disruptions in this microbial community, or dysbiosis, can directly contribute to HPA axis dysfunction and metabolic disease. Therefore, advanced nutritional strategies are aimed at cultivating a healthy gut ecosystem and leveraging specific dietary compounds, like polyphenols, to fine-tune the body’s stress and metabolic response at a cellular level.

How Does the Gut Microbiome Regulate the HPA Axis?

The gut microbiome communicates with the brain and adrenal glands through several sophisticated pathways. Gut bacteria produce a vast array of metabolites, including short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate, propionate, and acetate, from the fermentation of dietary fiber.

These SCFAs can cross the blood-brain barrier and directly influence the function of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland, thereby modulating the stress response. Butyrate, for example, has been shown to support the integrity of the intestinal barrier, reducing the translocation of inflammatory molecules like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into the bloodstream.

LPS is a potent activator of the immune system and the HPA axis, and preventing its entry into circulation is a key mechanism by which a healthy gut protects against chronic stress.

Furthermore, the gut microbiota is responsible for synthesizing a significant portion of the body’s neurotransmitters, including serotonin and GABA, both of which have calming effects on the nervous system and can buffer the stress response.

A diet rich in diverse sources of prebiotic fiber ∞ from foods like asparagus, garlic, onions, and Jerusalem artichokes ∞ provides the necessary substrate for these beneficial bacteria to thrive. This cultivation of a healthy microbiome is a primary, upstream strategy for maintaining HPA axis and metabolic balance.

Targeting the gut microbiome with specific fibers and fermented foods provides a direct route to modulating the neuro-inflammatory signals that govern adrenal and metabolic function.

The Molecular Impact of Polyphenols on Metabolic Health

Polyphenols are a class of phytochemicals found in colorful plants, fruits, and vegetables that exert profound effects on human physiology. Their benefits extend far beyond their antioxidant capacity. These molecules can influence metabolic health by interacting with key enzymes and signaling pathways.

For instance, certain polyphenols, like quercetin (found in apples and onions) and resveratrol (found in grapes), can activate a pathway known as AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK). AMPK is often called the body’s “master metabolic switch.” Its activation improves insulin sensitivity, enhances glucose uptake into cells, and promotes the burning of fat for energy.

In the context of adrenal-metabolic health, the anti-inflammatory properties of polyphenols are particularly relevant. Chronic stress drives inflammation, which can lead to glucocorticoid resistance, a state where cells become less responsive to cortisol’s signals. This can result in a dysfunctional HPA axis that continues to produce high levels of cortisol in a futile attempt to quell inflammation.

Polyphenols can help break this cycle by inhibiting pro-inflammatory signaling pathways, such as NF-κB, thereby restoring cellular sensitivity to cortisol and promoting a more balanced stress response. A diet that emphasizes a wide variety of deeply colored plants ∞ such as berries, dark leafy greens, and spices like turmeric ∞ delivers a rich array of these powerful signaling molecules.

| Nutrient/Compound | Primary Source | Molecular Mechanism of Action | Physiological Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Omega-3 Fatty Acids (EPA/DHA) | Fatty fish, algae oil | Incorporation into cell membranes, reducing inflammatory eicosanoid production and modulating HPA axis signaling. | Reduced systemic inflammation; improved cortisol sensitivity. |

| Prebiotic Fibers (e.g. Inulin, FOS) | Chicory root, garlic, onions, leeks | Fermented by gut bacteria to produce SCFAs like butyrate, which strengthens the gut barrier and signals to the brain. | Enhanced gut barrier function; reduced LPS translocation; modulated HPA axis activity. |

| Polyphenols (e.g. Quercetin, Curcumin) | Apples, berries, turmeric, green tea | Activation of AMPK pathway; inhibition of pro-inflammatory NF-κB signaling. | Improved insulin sensitivity; reduced oxidative stress and inflammation. |

| L-Theanine | Green tea | Increases alpha brain wave activity and may modulate neurotransmitter levels (GABA, dopamine, serotonin). | Promotes a state of calm alertness; buffers the psychological perception of stress. |

References

- Stimson, Roland H. et al. “Dietary macronutrient content alters cortisol metabolism independently of body weight changes in obese men.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 92, no. 11, 2007, pp. 4480-4484.

- Cryan, John F. et al. “The microbiota-gut-brain axis.” Physiological Reviews, vol. 99, no. 4, 2019, pp. 1877-2013.

- Matin, A. et al. “Tracking metabolic responses based on macronutrient consumption ∞ A comprehensive study to continuously monitor and quantify dual markers (cortisol and glucose) in human sweat using WATCH sensor.” Biosensors and Bioelectronics, vol. 223, 2023, p. 115014.

- Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. “Stress, food, and inflammation ∞ psychoneuroimmunology and nutrition at the cutting edge.” Psychosomatic Medicine, vol. 72, no. 4, 2010, pp. 365-369.

- Turtzi, E. et al. “The Effects of Polyphenol Intake on Metabolic Syndrome ∞ Current Evidences from Human Trials.” Current Pharmaceutical Design, vol. 24, no. 2, 2018, pp. 182-195.

- Karl, J. P. et al. “Effects of psychological, environmental and physical stressors on the gut microbiota.” Frontiers in Microbiology, vol. 9, 2018, p. 2013.

- Weickert, Martin O. and Andreas F. H. Pfeiffer. “Metabolic effects of dietary fiber consumption and prevention of diabetes.” The Journal of Nutrition, vol. 138, no. 3, 2008, pp. 439-442.

- Godos, J. et al. “The role of polyphenols in the management of the metabolic syndrome ∞ A systematic review of meta-analyses of randomized clinical trials.” Phytotherapy Research, vol. 35, no. 12, 2021, pp. 6658-6673.

- Clapp, Megan, et al. “Gut microbiota’s effect on mental health ∞ The gut-brain axis.” Clinics and Practice, vol. 7, no. 4, 2017, p. 987.

- Speers, A. B. et al. “Effects of adaptogens on the central nervous system and the molecular mechanisms associated with their stress-protective activity.” Pharmaceuticals, vol. 14, no. 10, 2021, p. 1026.

Reflection

A Personal Biological Narrative

The information presented here offers a map of the intricate biological landscape that governs your energy, resilience, and vitality. It connects the symptoms you may be experiencing to the underlying systems responsible for them. This knowledge is the first, most critical step.

The journey toward reclaiming balance is a personal one, guided by the unique signals your body provides. Consider the patterns in your own life. When does your energy falter? What are your cravings communicating? How does your body respond to different types of foods and different forms of stress?

Understanding these connections transforms you from a passive recipient of symptoms into an active participant in your own health narrative. The principles of adrenal-metabolic nutrition are not a rigid prescription, but a set of tools to help you listen more closely to your body’s wisdom.

The ultimate goal is to cultivate a way of eating and living that restores the innate intelligence of your own biological systems, allowing you to function with clarity and vigor. This process of self-discovery, supported by science, is the foundation of profound and lasting wellness.