Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A persistent fatigue that sleep doesn’t resolve, a subtle shift in your mood that seems disconnected from your daily life, or a change in your body’s composition that diet and exercise no longer seem to influence.

This experience, this sense of being metabolically out of sync, is a valid and deeply personal starting point. Your body is communicating a change in its internal state, and understanding the language it speaks is the first step toward reclaiming your vitality. That language is the language of hormones, and the foods you consume are the vocabulary.

The endocrine system is your body’s sophisticated internal messaging service. It consists of glands that produce and release hormones, which are chemical messengers that travel through the bloodstream to tissues and organs, dictating their function. These messages regulate nearly every process in your body, from your metabolic rate and sleep cycles to your stress response and reproductive health.

To function correctly, this system requires specific raw materials. Your dietary intake provides the fundamental building blocks for every single hormone your body produces.

The Building Blocks of Hormones

Hormones are synthesized from two primary types of molecules ∞ proteins and lipids (fats). This biological fact has direct implications for your plate. Peptide hormones, such as insulin which regulates blood sugar, and growth hormone which influences cellular repair, are constructed from amino acids. These are the very same amino acids you consume from protein-rich foods.

Steroid hormones, which include the sex hormones testosterone and estrogen, as well as the stress hormone cortisol, are derived from cholesterol. Consuming healthy fats is therefore a prerequisite for producing these essential signaling molecules. A diet chronically low in quality fats can deprive your body of the necessary substrates to maintain adequate levels of these hormones, impacting everything from libido and muscle mass to mood and inflammation.

Micronutrients the Essential Production Crew

If macronutrients are the raw materials, micronutrients ∞ vitamins and minerals ∞ are the specialized tools and assembly line workers. They act as cofactors, essential helpers for the enzymes that drive the conversion of those raw materials into finished, active hormones. Without them, the production process grinds to a halt.

- Iodine and Selenium ∞ These minerals are indispensable for thyroid health. The thyroid gland produces hormones that act as the body’s master metabolic regulator. Iodine is a direct component of thyroid hormones (T4 and T3), while selenium is required for the enzyme that converts the less active T4 into the more potent T3.

- Zinc ∞ This mineral is a critical player in male reproductive health, as it is directly involved in the synthesis of testosterone. Low zinc levels can contribute to symptoms associated with low testosterone.

- B Vitamins ∞ The B-complex vitamins, particularly B5 (pantothenic acid) and B6, are vital for the function of the adrenal glands. These glands produce cortisol and DHEA, the hormones that mediate your stress response. Chronic stress can deplete B vitamins, impairing the body’s ability to manage its stress response effectively.

- Vitamin D ∞ Functioning more like a hormone itself, Vitamin D is crucial for overall endocrine health. Its receptors are found in numerous endocrine tissues, including the thyroid and pancreas, indicating its wide-ranging regulatory roles.

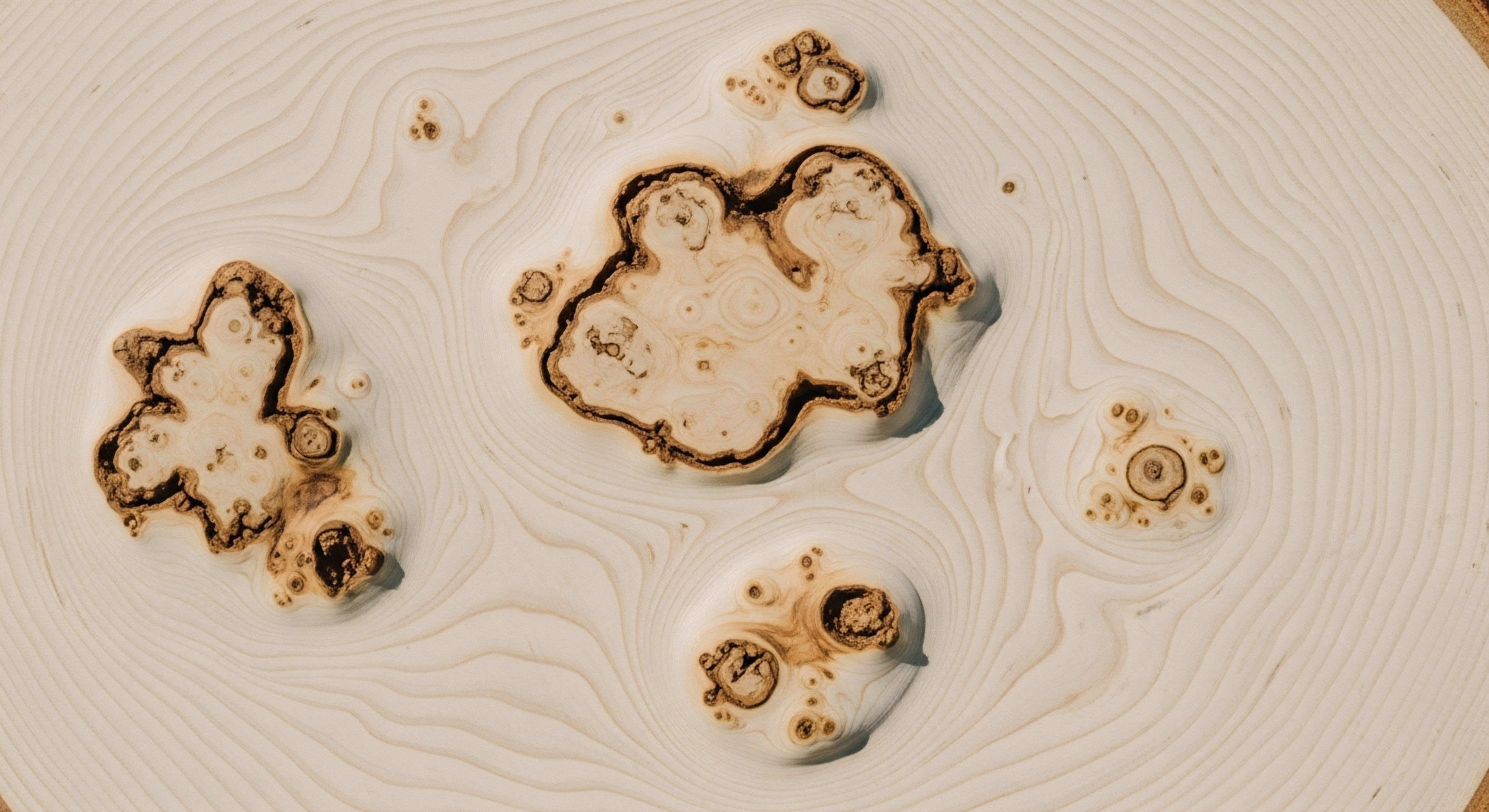

Your body constructs its essential hormonal messengers directly from the proteins, fats, and micronutrients you consume.

Blood Sugar and Insulin a Core Relationship

Perhaps the most immediate and impactful way diet influences the endocrine system is through the regulation of blood sugar and insulin. When you consume carbohydrates, they are broken down into glucose, which enters the bloodstream. In response, the pancreas, an endocrine gland, releases insulin. Insulin’s job is to shuttle glucose out of the blood and into cells to be used for energy.

A dietary pattern high in refined carbohydrates and sugars forces the pancreas to work overtime, leading to chronically high levels of insulin. This state, known as hyperinsulinemia, can cause cells to become less responsive to insulin’s signals, a condition called insulin resistance. Insulin resistance is a major disruptor of endocrine function.

It is linked to a cascade of other hormonal issues, including altered cortisol rhythms, imbalances in sex hormones, and increased inflammation, which further disrupts cellular communication throughout the body. Stabilizing blood sugar through a diet rich in fiber, protein, and healthy fats is a foundational step in supporting the entire endocrine network.

Understanding these fundamental connections demystifies the link between what you eat and how you feel. It shifts the focus from calories to communication. The food you choose is a powerful tool for providing your body with the precise instructions it needs to build, regulate, and restore its own intricate hormonal balance. This is the starting point of the journey ∞ a conscious effort to supply your biological systems with the high-quality information they need to function without compromise.

Intermediate

Moving beyond the foundational building blocks of hormones, we can begin to analyze how specific, consistent dietary patterns orchestrate a symphony of endocrine responses. Your daily food choices, when aggregated over time, create a distinct metabolic environment. This environment can either promote clear, efficient hormonal signaling or generate static and interference that disrupts communication.

Two dietary patterns stand in stark contrast in their effects on this environment ∞ the Western diet and the Mediterranean diet. Examining their composition reveals how profoundly different nutritional philosophies translate into different hormonal outcomes.

The Western dietary pattern, characterized by high intakes of processed foods, refined sugars, and saturated fats, is pro-inflammatory and a primary driver of insulin resistance. This pattern has been associated with hormonal imbalances such as reduced testosterone levels and impaired reproductive function.

It creates a state of low-grade systemic inflammation, which is like trying to have a conversation in a crowded, noisy room. The messages sent by your hormones are still being produced, but their ability to be heard and acted upon by their target cells is significantly diminished.

The Mediterranean Diet a Blueprint for Hormonal Communication

The Mediterranean diet offers a compelling alternative, functioning as a blueprint for creating an environment of clear hormonal signaling. This dietary pattern is defined by a high consumption of fruits, vegetables, legumes, whole grains, fish, and olive oil, with low consumption of red meat. Its benefits extend far beyond cardiovascular health, directly influencing several endocrine axes.

The anti-inflammatory nature of this diet is one of its key attributes. The abundance of omega-3 fatty acids from fish and polyphenols from olive oil, fruits, and vegetables actively reduces systemic inflammation. This quiets the “noise” in the system, enhancing the sensitivity of hormone receptors.

When receptors are more sensitive, the body can respond more efficiently to its own hormonal cues. For individuals on hormonal optimization protocols, such as Testosterone Replacement Therapy (TRT), this can be particularly meaningful. An anti-inflammatory environment may enhance the body’s responsiveness to therapy, allowing for more effective symptom resolution.

A Mediterranean dietary pattern provides a rich source of anti-inflammatory compounds that enhance the sensitivity of cellular hormone receptors.

How Does This Diet Influence Specific Hormones?

The mechanisms are multifaceted. The high fiber content of the Mediterranean diet slows the absorption of glucose, promoting stable blood sugar and insulin levels. This prevents the hormonal cascade associated with insulin resistance. Furthermore, the diet has been shown to improve both male and female reproductive health and is associated with a decreased risk of thyroid disorders.

The healthy fats and micronutrients it provides are the direct precursors for sex hormone and thyroid hormone production, ensuring the body has an ample supply of raw materials.

| Component | Typical Western Diet | Mediterranean Diet | Primary Hormonal Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fat Source | High in saturated and trans fats (processed foods, red meat) | High in monounsaturated and polyunsaturated fats (olive oil, nuts, fish) | Western pattern promotes inflammation and insulin resistance. Mediterranean pattern provides building blocks for steroid hormones and reduces inflammation. |

| Carbohydrate Source | High in refined grains and added sugars | High in whole grains, legumes, and fruits (high fiber) | Western pattern leads to insulin spikes and resistance. Mediterranean pattern supports stable blood sugar and insulin sensitivity. |

| Micronutrient Density | Often low due to processing | High in vitamins, minerals, and polyphenols from fresh produce | Mediterranean pattern provides essential cofactors for hormone synthesis (e.g. zinc, selenium) and antioxidant protection. |

| Inflammatory Potential | High (pro-inflammatory) | Low (anti-inflammatory) | Western pattern disrupts hormonal signaling. Mediterranean pattern enhances hormone receptor sensitivity. |

The Gut Microbiome the Hidden Endocrine Organ

An even deeper layer of control involves the trillions of microorganisms residing in your gut. The gut microbiome is now understood to be a dynamic and influential endocrine organ in its own right. It actively communicates with and modulates your body’s primary hormonal systems. This communication happens through several pathways, but one of the most critical is the metabolism of hormones themselves.

A specific collection of gut bacteria, known as the “estrobolome,” produces an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase. This enzyme’s function is to deconjugate, or reactivate, estrogens that have been processed by the liver and are on their way to being excreted. A healthy, diverse estrobolome helps maintain estrogen balance.

However, an imbalanced gut microbiome (dysbiosis) can lead to either too much or too little beta-glucuronidase activity. This can result in the reabsorption of excess estrogen, contributing to conditions of estrogen dominance, or the insufficient reabsorption of estrogen, leading to deficiency. This gut-driven mechanism has profound implications for both men and women, influencing everything from menstrual cycles and menopausal symptoms to the risk of estrogen-related conditions.

Feeding Your Microbiome for Hormonal Balance

Dietary patterns directly shape the composition of the gut microbiome. A diet high in processed foods and low in fiber can starve beneficial bacteria, allowing less favorable species to proliferate. Conversely, a diet rich in diverse types of fiber from vegetables, fruits, and legumes acts as a prebiotic, providing the necessary fuel for a healthy microbiome to flourish.

- Prebiotics ∞ These are non-digestible fibers that feed beneficial gut bacteria. Sources include garlic, onions, asparagus, and whole grains.

- Probiotics ∞ These are live beneficial bacteria found in fermented foods like yogurt, kefir, sauerkraut, and kimchi. They can help replenish and diversify the gut microbial community.

By adopting a dietary pattern that supports gut health, such as the Mediterranean diet, you are also directly supporting the regulation of your sex hormones. This is a powerful example of the interconnectedness of bodily systems.

For a man on a TRT protocol that includes Anastrozole to manage estrogen conversion, a healthy gut that supports proper estrogen metabolism could be a complementary strategy for maintaining hormonal equilibrium. Similarly, for a woman experiencing perimenopausal symptoms, optimizing gut health could help buffer against the dramatic hormonal fluctuations of this transition.

What about Phytoestrogens?

Phytoestrogens are compounds found in plants, particularly soy and flaxseed, that have a chemical structure similar to human estrogen. This allows them to bind to estrogen receptors in the body. Their effect is complex and appears to depend on the individual’s own hormonal status.

In individuals with low estrogen levels, such as postmenopausal women, phytoestrogens may exert a mild estrogenic effect, potentially alleviating some symptoms. In those with high estrogen levels, they may act as antagonists, blocking the effects of more potent endogenous estrogen.

The research on phytoestrogens is varied, and their impact is influenced by factors like the type and amount consumed, as well as an individual’s gut microbiome, which is responsible for converting these compounds into their active forms. For many, incorporating whole-food sources of phytoestrogens, like flaxseed and fermented soy, as part of a balanced diet can be a supportive measure. However, their use as concentrated supplements warrants a more cautious and personalized approach.

Ultimately, an intermediate understanding of diet and endocrine health moves toward a systems-based view. It recognizes that dietary patterns like the Mediterranean diet work because they address multiple interconnected systems at once ∞ they reduce inflammation, stabilize insulin, provide essential hormonal building blocks, and nourish the gut microbiome. This integrated approach creates a robust foundation upon which the body’s own regulatory systems, and any clinical protocols, can function with maximal efficacy.

Academic

A sophisticated examination of nutritional endocrinology requires a shift in perspective, viewing the gut microbiome not merely as a digestive organ but as a distributed, signal-transducing superorganism that functions as a primary endocrine regulator.

The metabolic output of the microbiota, particularly the production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), constitutes a major signaling network that directly modulates host energy homeostasis, immune function, and the activity of multiple endocrine axes. This deep dive moves beyond dietary patterns to the specific molecular mechanisms by which microbial metabolites orchestrate host physiology.

Short-Chain Fatty Acids as Primary Endocrine Signals

SCFAs, principally acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are produced by the anaerobic fermentation of dietary fiber by gut bacteria, predominantly from the phyla Firmicutes and Bacteroidetes. These molecules are not simply metabolic byproducts; they are potent signaling molecules that interact with a class of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs), namely FFAR2 (GPR43) and FFAR3 (GPR41), expressed on various host cells, including enteroendocrine cells (EECs).

EECs are specialized sensory cells scattered throughout the intestinal epithelium. Upon activation by SCFAs, EECs release a host of peptide hormones that have systemic effects. A key example is the release of glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY) from L-cells.

- GLP-1 ∞ This incretin hormone potentiates glucose-stimulated insulin secretion from pancreatic β-cells, suppresses glucagon secretion, slows gastric emptying, and promotes satiety via central nervous system pathways. The microbial production of SCFAs is therefore a direct upstream regulator of glycemic control.

- PYY ∞ Released postprandially, PYY acts on the hypothalamic arcuate nucleus to reduce appetite and food intake.

Butyrate, in addition to its role as a signaling molecule, is the primary energy source for colonocytes and has a critical role in maintaining gut barrier integrity and exhibiting histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitory activity, which has epigenetic implications for gene expression.

A diet deficient in fermentable fiber starves the microbiota of the substrate needed to produce these vital signaling molecules, contributing to insulin resistance, impaired satiety signaling, and gut barrier dysfunction ∞ a state often termed “leaky gut.” This increased intestinal permeability allows for the translocation of inflammatory bacterial components like lipopolysaccharide (LPS) into systemic circulation, driving the low-grade inflammation that underpins many metabolic and endocrine disorders.

Microbial Modulation of the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis

The gut-brain axis is a bidirectional communication system, and the microbiome is a key regulator of its function, including the stress-responsive Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis. The microbiota can influence the HPA axis at central and peripheral levels. Germ-free animal models exhibit an exaggerated HPA response to stress, a finding that can be normalized by colonization with specific bacterial species, such as Bifidobacterium infantis.

The mechanisms are complex, involving microbial production of neurotransmitters (e.g. GABA, serotonin) that can signal via the vagus nerve, and the influence of SCFAs on central processes. Chronic gut dysbiosis can contribute to HPA axis dysregulation, characterized by altered cortisol secretion patterns.

This has direct relevance for individuals with symptoms of adrenal fatigue or burnout, where restoring a healthy gut ecosystem through targeted nutrition (high-fiber, fermented foods) becomes a primary therapeutic target. This also has implications for peptide therapies. The function of growth hormone secretagogues like Tesamorelin or CJC-1295/Ipamorelin depends on a responsive pituitary gland. A dysregulated HPA axis, influenced by gut dysbiosis, can create an environment of “pituitary resistance,” potentially blunting the efficacy of these protocols.

Microbial-derived short-chain fatty acids act as primary signaling molecules, directly stimulating enteroendocrine cells to release systemic hormones like GLP-1.

The Microbiome’s Role in Sex Hormone Homeostasis

The academic view of the estrobolome expands to include the broader regulation of steroid hormones. Gut microbes can influence circulating levels of androgens and estrogens through several mechanisms beyond the direct metabolism of estrogens.

The gut microbiota regulates the enterohepatic circulation of sex steroids. After conjugation in the liver (a process that marks them for excretion), these hormones are secreted into the gut via bile. Gut bacteria can deconjugate these steroids, allowing them to be reabsorbed into circulation.

An imbalance in the microbiome can thus alter the systemic pool of active sex hormones. Furthermore, gut dysbiosis and associated LPS-driven inflammation can negatively impact testicular Leydig cell function and ovarian function, impairing the primary production of testosterone and estrogen, respectively.

This creates a feedback loop. Sex hormones themselves also shape the composition of the gut microbiome. Estrogen, for example, is known to enhance gut barrier function and microbial diversity. The decline in estrogen during menopause can contribute to decreased microbial diversity and increased gut permeability, potentially exacerbating inflammatory symptoms.

This highlights the interconnectedness that must be appreciated when designing therapeutic protocols. For a man on TRT, or a woman on a post-menopausal protocol of Testosterone and Progesterone, optimizing the gut microbiome is not an adjunct therapy; it is a foundational strategy to ensure the hormonal environment is optimized at every level of regulation.

| Microbial Metabolite/Component | Primary Microbial Source | Host Target/Receptor | Endocrine Consequence | Clinical Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Butyrate, Propionate, Acetate (SCFAs) | Fermentation of fiber by Firmicutes, Bacteroidetes | FFAR2, FFAR3 on L-cells | Increased secretion of GLP-1 and PYY. | Improved insulin sensitivity, glycemic control, and satiety signaling. |

| Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) | Gram-negative bacteria (e.g. Enterobacteriaceae) | Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) | Pro-inflammatory cytokine cascade, insulin resistance. | Drives low-grade systemic inflammation, disrupts multiple endocrine axes. |

| Beta-glucuronidase (Enzyme) | E. coli, Bacteroidetes, Firmicutes | Conjugated estrogens in the gut | Deconjugation and reabsorption of estrogens. | Modulation of circulating estrogen levels; imbalance linked to estrogen dominance. |

| Tryptophan Metabolites | Clostridium, Lactobacillus species | Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) | Modulation of immune cells and gut barrier integrity. | Regulation of gut inflammation, which indirectly affects all endocrine systems. |

In conclusion, a scientifically rigorous approach to dietary endocrinology must be grounded in the molecular dialogues between the host and its microbiome. Dietary patterns derive their efficacy from their ability to modulate this dialogue. A diet rich in complex, fermentable fibers is a direct method of selecting for a beneficial microbial community that produces signaling molecules like SCFAs.

This, in turn, promotes euglycemia, reduces inflammation, and supports the healthy metabolism of steroid hormones. This systems-biology perspective provides the rationale for prioritizing gut health as a central pillar in any advanced clinical protocol aimed at hormonal and metabolic optimization. It explains why nutrition is the bedrock upon which therapies like TRT, peptide protocols, and female hormonal recalibration are built.

References

- Rinaldi, S. et al. “Diet, nutrition and cancer ∞ the future of research in the WHO European Region.” European Journal of Cancer Prevention, vol. 25, no. 1, 2016, pp. 1-8.

- He, S. et al. “Gut mycobiota and its interactions with the host ∞ a new frontier in immunopathology.” Cellular & Molecular Immunology, vol. 18, no. 5, 2021, pp. 1125-1137.

- Martin, A. M. et al. “The gut microbiome and enteroendocrine cells ∞ a new therapeutic target in obesity and diabetes.” Current Diabetes Reports, vol. 18, no. 11, 2018, p. 117.

- Barrea, L. et al. “Role of Mediterranean diet in endocrine diseases ∞ a joint overview by the endocrinologist and the nutritionist.” Reviews in Endocrine and Metabolic Disorders, vol. 24, no. 2, 2023, pp. 203-221.

- Patil, M. “The role of the gut microbiome in regulating the endocrine system.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 107, no. 5, 2022, pp. 1469-1481.

- Sleiman, D. et al. “The role of the gut microbiome in the regulation of the HPA axis and stress.” Frontiers in Endocrinology, vol. 13, 2022, p. 1000451.

- Qi, X. et al. “Gut microbiota-bile acid-interleukin-22 axis orchestrates polycystic ovary syndrome.” Nature Medicine, vol. 25, no. 8, 2019, pp. 1225-1233.

- Adlercreutz, H. & Mazur, W. “Phyto-oestrogens and Western diseases.” Annals of Medicine, vol. 29, no. 2, 1997, pp. 95-120.

- Sarkar, A. et al. “Gut microbiome and depressive symptomatology ∞ a systematic review of the literature.” Journal of Affective Disorders, vol. 241, 2018, pp. 363-376.

- Cani, P. D. et al. “Changes in gut microbiota control metabolic endotoxemia-induced inflammation in high-fat diet-induced obesity and diabetes in mice.” Diabetes, vol. 57, no. 6, 2008, pp. 1470-1481.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Environment

The information presented here provides a map of the intricate connections between your nutritional choices and your internal hormonal landscape. You have seen how the molecules in your food become the messengers that govern your physiology, how entire dietary patterns can either clarify or disrupt that communication, and how the vast ecosystem within you actively participates in this dialogue.

This knowledge is a form of power. It shifts the narrative from one of passive suffering from symptoms to one of active participation in your own biological calibration.

Consider your own lived experience. The fatigue, the mood shifts, the physical changes ∞ these are signals. They are data points originating from a complex system seeking balance. Where on this map do your experiences seem to land? Does the concept of inflammatory noise resonate with how you feel?

Does the idea of an imbalanced internal ecosystem align with your symptoms? This process of self-inquiry is the critical next step. The journey toward optimized health is deeply personal, built upon a foundation of universal biological principles but ultimately tailored to your unique genetic makeup, lifestyle, and history. The path forward involves using this knowledge not as a rigid set of rules, but as a lens through which to view your own body’s signals with greater clarity and intention.

Glossary

endocrine system

blood sugar

signaling molecules

steroid hormones

thyroid health

insulin resistance

sex hormones

hormonal signaling

dietary patterns

mediterranean diet

systemic inflammation

fatty acids

gut microbiome

estrobolome

gut health

phytoestrogens

short-chain fatty acids

gut barrier