Fundamentals

The decision to discontinue a hormonal optimization protocol represents a significant transition for your body’s internal environment. You may be feeling a sense of uncertainty, wondering how and when your natural systems will resume their previous functions. This experience is a valid and common part of the process.

Your body has been receiving external signals, and now it must recalibrate its own internal communication network. Understanding the architecture of this system is the first step toward navigating this phase with confidence.

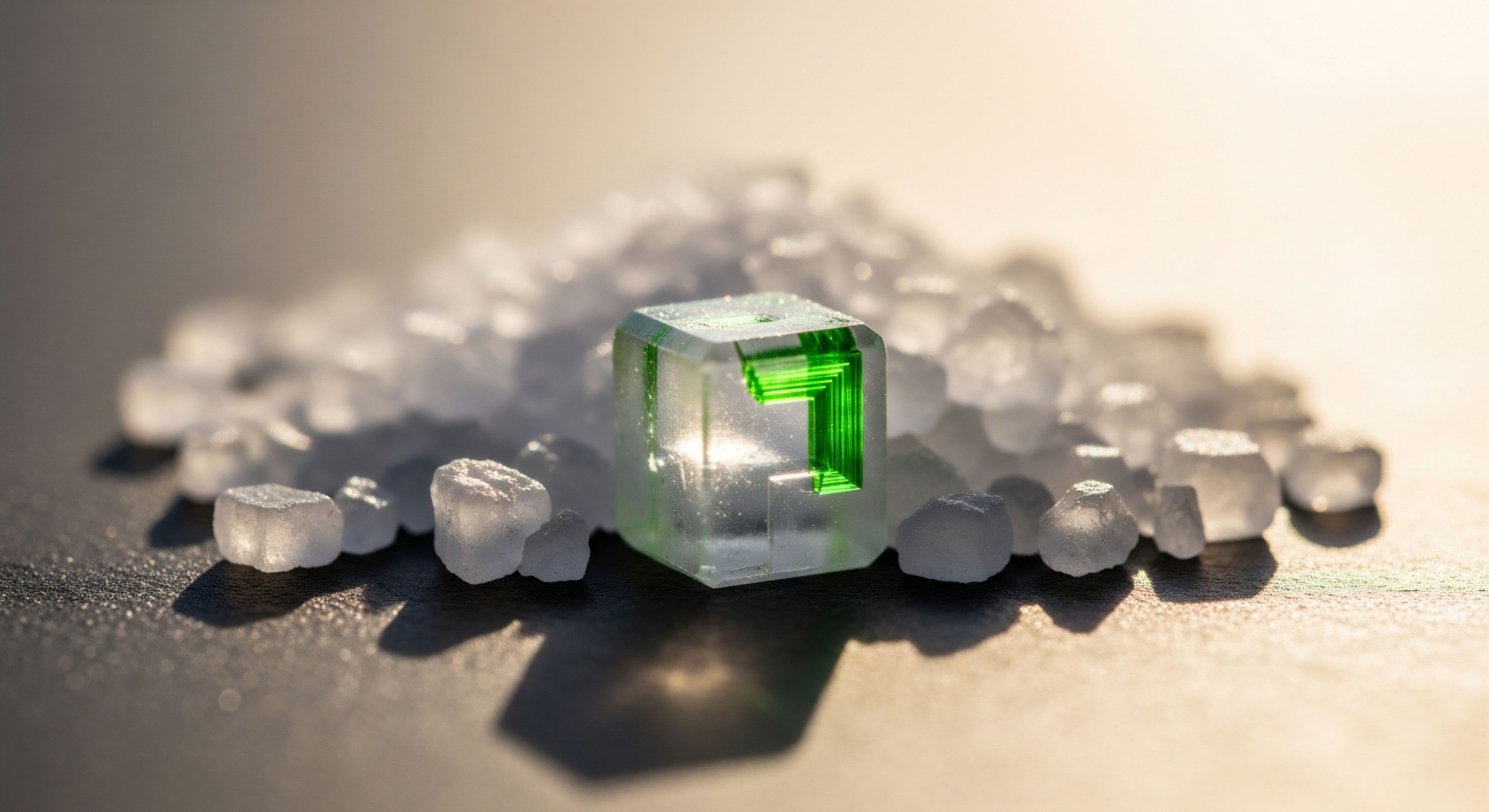

At the center of this recalibration is a sophisticated biological feedback loop known as the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis. Think of this as the primary command and control system for your endocrine health. It is a continuous conversation between three distinct anatomical structures, each with a specific role in governing hormonal production and reproductive function.

The Command Center the Hypothalamus

The hypothalamus, a small region located at the base of the brain, acts as the system’s primary sensor. It constantly monitors the levels of hormones circulating in your bloodstream, including testosterone. When it detects that testosterone levels are within their optimal range, it remains relatively quiet.

When levels of exogenous testosterone are introduced, the hypothalamus interprets this as a signal that the body has more than enough. In response, it reduces or completely halts its own stimulating signal, a hormone called Gonadotropin-Releasing Hormone (GnRH). This is a protective mechanism, designed to maintain equilibrium. During a therapeutic protocol, this reduction is the intended effect; upon cessation, the system must learn to send its signals once again.

The Messenger the Pituitary Gland

GnRH from the hypothalamus travels a very short distance to the pituitary gland, which can be considered the master messenger. The pituitary responds to GnRH by producing and releasing two critical signaling hormones into the bloodstream:

- Luteinizing Hormone (LH) ∞ In males, LH travels to the Leydig cells within the testes. Its primary instruction is to stimulate the production of endogenous testosterone. Without the LH signal, the testes’ internal testosterone factories slow their production.

- Follicle-Stimulating Hormone (FSH) ∞ FSH also targets the testes, specifically the Sertoli cells. These cells are the primary nurturers of sperm production, a complex process called spermatogenesis. FSH is the direct signal that initiates and maintains a healthy environment for sperm to develop and mature.

When exogenous testosterone is present, the suppression of GnRH leads to a downstream suppression of both LH and FSH. The result is a dual-effect shutdown ∞ internal testosterone production diminishes, and the machinery of spermatogenesis is paused. This is why fertility is impacted during androgen therapy. The system is not broken; it is simply responding to the information it is receiving from its environment.

The Production Facility the Gonads

The testes are the final destination for the pituitary’s messages. They are responsible for both producing testosterone and manufacturing sperm. Their function is entirely dependent on receiving clear, consistent signals from LH and FSH. When these signals are absent for a prolonged period, the testicular machinery can become dormant. The volume of the testes may decrease, reflecting a state of reduced activity within the Leydig and Sertoli cells. The recovery process is centered on reawakening these cellular factories.

The journey to restoring natural spermatogenesis is a process of re-establishing the delicate hormonal dialogue within the body’s HPG axis.

Understanding this biological sequence provides a clear framework for what happens post-therapy. The timeline for recovery is directly linked to how quickly and efficiently this three-part communication system can be restored. The challenge lies in encouraging the hypothalamus to resume sending GnRH, prompting the pituitary to release LH and FSH, and signaling the testes to respond to those commands.

Each individual’s timeline is influenced by a unique set of biological factors that determine the pace of this systemic recalibration.

Intermediate

As the body begins the process of recalibrating the HPG axis, the timeline for the return of spermatogenesis is not arbitrary. It is governed by a set of identifiable and measurable biological variables. These factors act as predictors, offering a clinical lens through which we can estimate the potential duration and success of the recovery phase.

For any man seeking to restore fertility after discontinuing androgen support, understanding these predictors is essential for setting realistic expectations and developing an effective clinical strategy.

The core principle of recovery is restarting a dormant system. The degree of that dormancy, and the underlying health of the system before it was paused, are the most significant determinants of the recovery trajectory. Clinical evidence has identified several key variables that consistently influence the time required to see a return of sperm in the ejaculate.

Key Predictors of Spermatogenesis Recovery

Several factors have a direct, measurable impact on the probability and timeline of sperm count restoration. These are not abstract concepts; they are concrete data points that can be assessed and used to inform a personalized recovery protocol.

- Age at Discontinuation ∞ Biological aging affects all cellular processes, including those within the testes. Older age at the time of therapy cessation is a consistent predictor of a longer recovery period. Research indicates that for every year of age, the probability of successful sperm recovery within a 12-month period decreases by a small but statistically significant margin. This reflects a natural decline in testicular resilience and responsiveness to stimulation.

- Duration of Exogenous Androgen Use ∞ The length of time the HPG axis has been suppressed is directly correlated with the time it takes to reactivate. A shorter duration of use, particularly less than one year, is associated with a higher probability of faster recovery. Conversely, long-term use over many years can lead to a more profound suppression that requires a more extended and sometimes more intensive recovery protocol.

- Baseline Testicular Volume ∞ The size of the testes prior to initiating any hormonal therapy serves as a proxy for their baseline functional capacity. A larger pre-therapy testicular volume often suggests a more robust potential for sperm production. This parameter can be a useful indicator of the testes’ innate ability to respond once stimulatory signals from the pituitary are restored.

- Presence of Azoospermia vs. Cryptozoospermia ∞ During therapy, some men may have a complete absence of sperm in the ejaculate (azoospermia), while others may have a severely reduced number (cryptozoospermia). Men who are cryptozoospermic tend to recover more quickly than those who are fully azoospermic, suggesting their spermatogenic processes were not as deeply suppressed.

Clinical Protocols for Accelerating Recovery

While spontaneous recovery is possible, it can be a lengthy and unpredictable process. For this reason, specific clinical protocols are employed to actively stimulate the HPG axis and accelerate the return of spermatogenesis. These protocols use medications that mimic or stimulate the body’s own signaling hormones.

The primary goal of these interventions is to bypass the suppressed hypothalamus and pituitary and directly stimulate the testes, or to encourage the pituitary to resume its function. The selection of agents depends on the individual’s specific hormonal profile and recovery goals.

Table of Recovery Predictors and Their Clinical Implications

| Predictor Variable | Clinical Implication | Associated Recovery Timeline |

|---|---|---|

| Age | Older age is associated with reduced testicular responsiveness and a slower recovery of the HPG axis. | Longer (Probability of recovery decreases with each year of age). |

| Duration of TRT | Longer-term suppression requires more time for the pituitary to regain sensitivity and resume LH/FSH production. | Longer (The impact is more pronounced in the initial 6 months post-cessation). |

| Baseline Testicular Health | Higher pre-therapy testicular volume and sperm counts suggest a more robust system capable of faster reactivation. | Shorter (Indicates a higher functional reserve). |

| Type of Suppression | The presence of some sperm (cryptozoospermia) indicates a less profound suppression than complete absence (azoospermia). | Shorter for cryptozoospermia compared to azoospermia. |

What Is the Role of HCG in Recovery Protocols?

Human Chorionic Gonadotropin (hCG) is a cornerstone of post-TRT recovery protocols. It is a biological mimic of Luteinizing Hormone (LH). When administered via injection, hCG bypasses the dormant pituitary and directly stimulates the Leydig cells in the testes. This action accomplishes two critical goals:

- It restarts intratesticular testosterone production, which is essential for spermatogenesis.

- The increased intratesticular testosterone helps restore testicular volume and function.

HCG therapy is often the first and most critical step in actively restarting the testicular machinery. Dosages are tailored to the individual, with common protocols involving injections two to three times per week.

Stimulating the Pituitary with SERMs

Another class of medications used are Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulators (SERMs), such as Clomiphene Citrate (Clomid) or Tamoxifen. These oral medications work at the level of the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. They block estrogen receptors in the brain, tricking the hypothalamus into thinking that estrogen levels are low.

Since estrogen also provides negative feedback to the HPG axis, blocking its effects encourages the hypothalamus to produce GnRH. This, in turn, stimulates the pituitary to release both LH and FSH. Using a SERM is a strategy to restart the entire axis from the top down, promoting the body’s own production of its signaling hormones.

A successful recovery strategy is built upon understanding individual predictors and applying targeted clinical protocols to restart the natural hormonal cascade.

Combining these approaches, such as using hCG to directly stimulate the testes while a SERM encourages the pituitary, can create a comprehensive strategy for recovery. Aromatase inhibitors like Anastrozole may also be used in certain cases to manage the conversion of testosterone to estrogen, further optimizing the hormonal environment for recovery. The path is methodical, grounded in the principles of endocrine function, and designed to systematically bring the system back online.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of spermatogenesis recovery post-androgen therapy moves beyond qualitative descriptions into the realm of quantitative modeling and cellular biology. The interruption of the HPG axis by exogenous testosterone is a predictable physiological event. The recovery from this state, however, is a complex interplay of individual genetic predispositions, cellular health, and the cumulative impact of supraphysiological androgen exposure over time.

A deep examination of the available clinical data allows for the construction of probabilistic models that can guide clinical decision-making with greater precision.

Quantitative Modeling of Recovery Probabilities

Recent cohort studies have provided the data necessary to develop linear probability models for spermatogenesis recovery. A notable study by Kohn et al. provides a quantitative framework for counseling men on their likelihood of recovery. The research analyzed a cohort of men who had discontinued testosterone therapy and were undergoing recovery protocols, primarily with hCG.

The primary endpoint was defined as achieving a total motile sperm count (TMC) of 5 million or greater, a threshold often considered sufficient for achieving unassisted conception.

The statistical analysis identified age and duration of therapy as the most powerful negative predictors of success. The regression analysis generated coefficients that quantify the precise impact of each variable. For recovery within 12 months, the model demonstrated that for each additional year of age, the probability of achieving the target TMC decreased by approximately 1.7%.

Similarly, for each additional year of testosterone use, the probability of recovery decreased by 3%. These figures are not abstract; they are direct statistical translations of biological reality.

Table of Modeled Recovery Probabilities

The following table is derived from the linear probability model developed by Kohn et al. illustrating the likelihood of achieving a total motile count greater than 5 million within 12 months of ceasing testosterone therapy. It visualizes the combined impact of age and duration of use.

| Age (Years) | Duration of TRT (Years) | Estimated Probability of Recovery at 12 Months |

|---|---|---|

| 30 | 1 | ~91% |

| 30 | 5 | ~79% |

| 40 | 1 | ~74% |

| 40 | 5 | ~62% |

| 50 | 1 | ~57% |

| 50 | 5 | ~45% |

This data underscores the durable, long-lasting effect of age on spermatogenic potential. The coefficient for age remained consistent when analyzing recovery at both 6 and 12 months. The impact of therapy duration, however, was more pronounced in the short term. Its negative coefficient was nearly halved when moving from the 6-month to the 12-month analysis, suggesting that with sufficient time, the suppressive effect of the therapy itself diminishes, while the biological limitations of age remain constant.

Why Does Preexisting Subfertility Matter so Much?

A critical factor that is more difficult to quantify but is of immense clinical importance is the individual’s baseline fertility status before ever initiating androgen therapy. Many men who seek testosterone optimization may have undiagnosed subfertility or a lower baseline testicular reserve.

In these cases, testosterone therapy does not cause the underlying issue, but it masks it and exacerbates it through HPG axis suppression. Upon cessation, the recovery process is not returning to a state of robust fertility, but to a pre-existing state of compromise.

This is why a thorough fertility history, and in some cases a baseline semen analysis before starting therapy, is a critical component of responsible endocrine management. Men who required a longer time to achieve conception prior to therapy may face a more challenging recovery path.

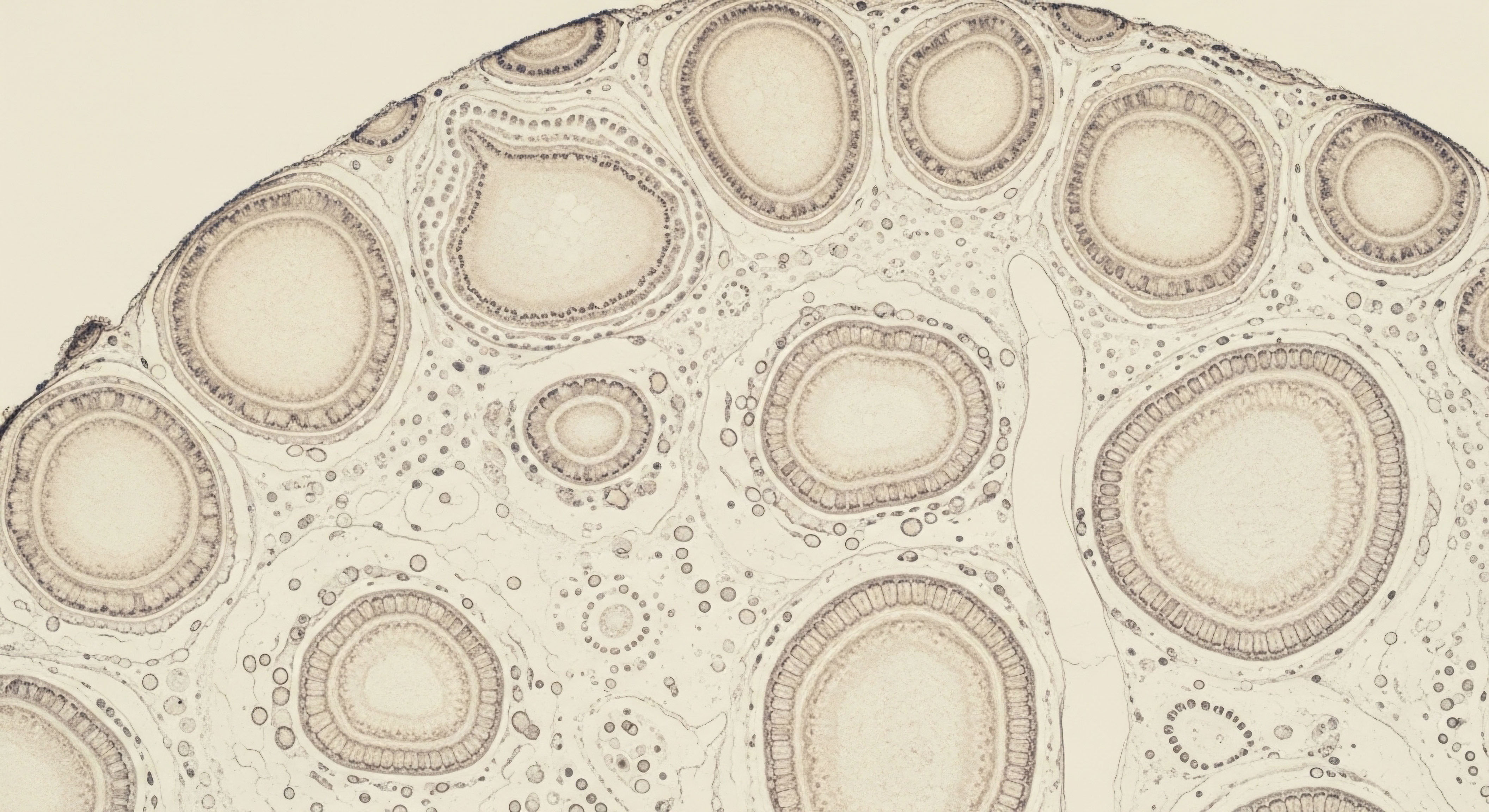

The Cellular Mechanics of Suppression and Recovery

At the microscopic level, the process is one of induced cellular dormancy. Spermatogenesis is a highly organized 74-day process that occurs within the seminiferous tubules of the testes. It is critically dependent on two factors ∞ FSH stimulation of the Sertoli cells and extremely high concentrations of intratesticular testosterone (ITT), often 50-100 times higher than blood levels.

Exogenous testosterone administration suppresses both LH and FSH. The loss of FSH signaling disrupts the supportive function of the Sertoli cells. The loss of LH signaling causes ITT levels to plummet, arresting the development of spermatids. The seminiferous tubules may shrink, and the intricate cellular architecture becomes disorganized.

The timeline for spermatogenesis recovery is a quantifiable probability influenced by age, therapy duration, and the underlying cellular health of the testicular environment.

Recovery protocols are a form of targeted cellular reactivation. HCG acts as an LH surrogate to restore high levels of ITT. This is the first and most vital step. The administration of SERMs or recombinant FSH aims to restore the function of the Sertoli cells.

The 74-day cycle of sperm production means that even after hormonal parameters in the blood have normalized, it can take three months or longer to see the results manifest in a semen analysis. The recovery is a biological process with an inherent, irreducible timeline dictated by the pace of human cell maturation.

References

- Kohn, T. P. et al. “Age and duration of testosterone therapy predict time to return of sperm count after human chorionic gonadotropin therapy.” Fertility and Sterility, vol. 106, no. 3, 2016, p. e37.

- Liu, P. Y. et al. “The rate, extent, and modifiers of spermatogenic recovery after hormonal contraception ∞ an integrated analysis.” The Lancet, vol. 363, no. 9419, 2004, pp. 1415-1423.

- Coward, R. M. et al. “Recovery of spermatogenesis following testosterone replacement therapy or anabolic-androgenic steroid use.” Asian Journal of Andrology, vol. 18, no. 3, 2016, pp. 373-380.

- Rassawala, M. et al. “Clinician’s guide to the management of azoospermia induced by exogenous testosterone or anabolic ∞ androgenic steroids.” Andrologia, vol. 55, no. 1, 2023, e14618.

- Wenker, E. P. et al. “The use of HCG-based combination therapy for recovery of spermatogenesis after testosterone use.” Journal of Sexual Medicine, vol. 12, no. 6, 2015, pp. 1334-1340.

- Rastrelli, G. et al. “Factors affecting spermatogenesis upon gonadotropin-replacement therapy ∞ a meta-analytic study.” Andrology, vol. 2, no. 6, 2014, pp. 794-808.

- Boron, W. F. & Boulpaep, E. L. Medical Physiology. 3rd ed. Elsevier, 2017.

- The Endocrine Society. “Testosterone Therapy in Men With Hypogonadism ∞ An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline.” Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 103, no. 5, 2018, pp. 1715-1744.

Reflection

The information presented here provides a map of the biological territory you are navigating. It translates the silent, internal processes of your body into a language of systems, signals, and probabilities. This knowledge is a tool, designed to move you from a position of uncertainty to one of informed action. You now have a clearer understanding of the dialogue between your brain and your endocrine system, and the factors that influence the pace of its restoration.

Consider the variables discussed. Reflect on your own personal health timeline and how these predictors might apply to your situation. This clinical data is the foundation, but your lived experience is the context that gives it meaning. The path forward involves integrating this scientific understanding with your personal health goals.

What Does This Mean for Your Path Forward?

Your journey is unique. The data provides a forecast, but it does not dictate the final outcome. The next step is to use this foundational knowledge to engage in a meaningful conversation with a clinical professional who specializes in endocrine health.

A personalized strategy, built on your specific hormonal profile and health history, is the most effective way to support your body’s return to its natural rhythm. You are the central figure in your health story, and with this understanding, you are better equipped to write the next chapter.