Fundamentals

You feel it before you can name it. A subtle shift in your energy, a change in your sleep patterns, a sense that your body’s internal rhythm is slightly off-key. This experience, this intimate and often frustrating dialogue with your own physiology, is the very starting point of understanding your endocrine system.

It is the vast, intricate communication network that governs everything from your mood to your metabolism. Your lived symptoms are valid data points, the first clues in a deeply personal investigation into your own biological blueprint. The journey to supporting this system begins with acknowledging these signals and learning to interpret their language.

We are not aiming to fight against the body, but to understand its requests and provide the foundational support it needs to recalibrate and function with renewed vitality.

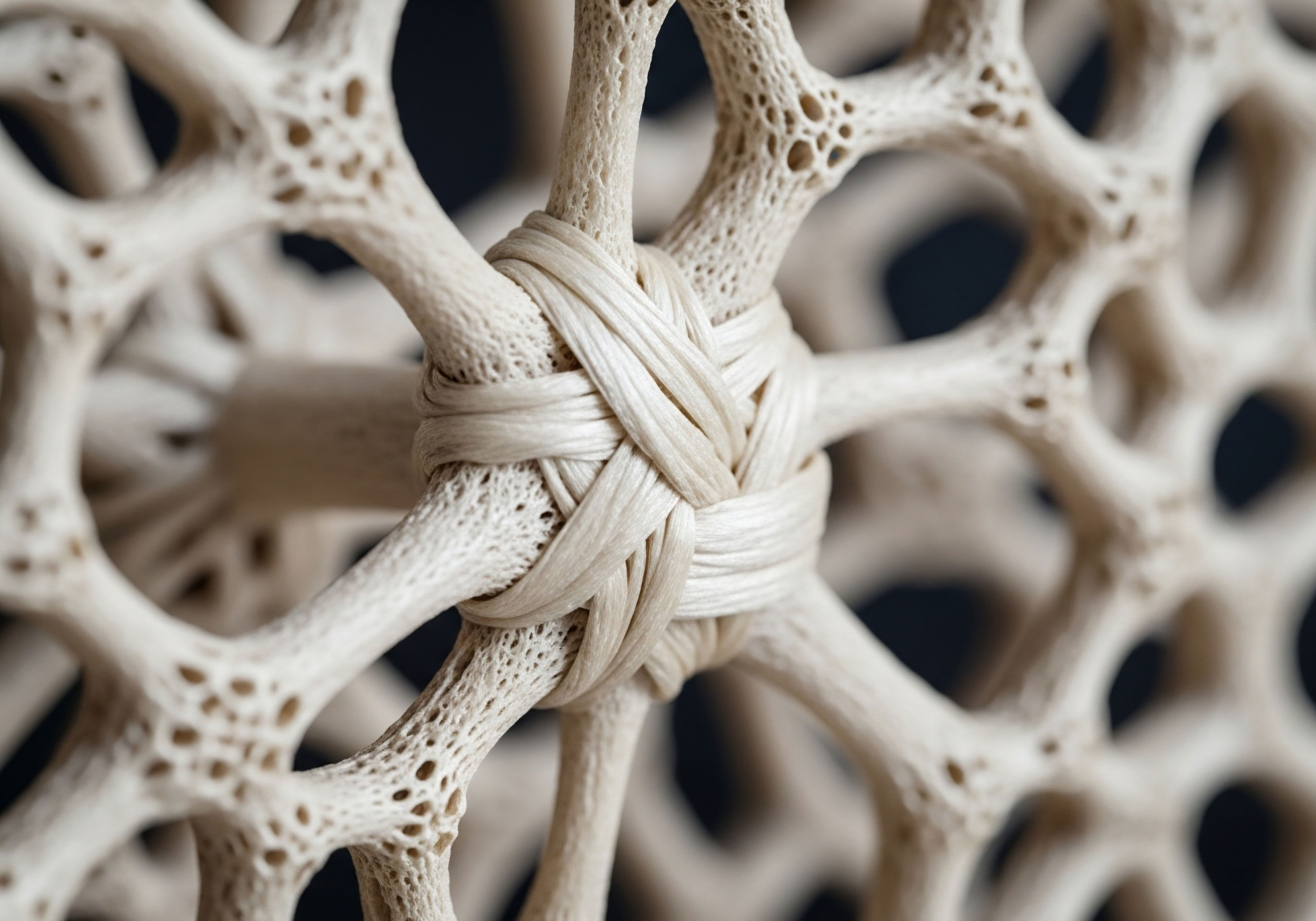

The endocrine system operates as the body’s internal postal service, dispatching chemical messengers called hormones through the bloodstream to instruct distant cells and organs on how to behave. This network of glands ∞ including the pituitary, thyroid, adrenals, pancreas, and gonads ∞ is responsible for orchestrating some of life’s most critical processes.

Think of it as a finely tuned orchestra, where each instrument must play in time and at the correct volume for the symphony of health to be harmonious. When one section is out of tune, the entire composition can be affected.

For instance, the thyroid gland, located in your neck, produces hormones that regulate your metabolic rate, influencing how quickly you burn calories and how energetic you feel. The adrenal glands, situated atop your kidneys, release cortisol in response to stress, a primal mechanism designed to prepare you for fight or flight. These are not abstract concepts; they are tangible, powerful forces shaping your daily reality.

The Core Pillars of Hormonal Well Being

Supporting this intricate system begins with the daily choices that create the environment in which your hormones are produced and regulated. These are the non-negotiable pillars upon which endocrine health is built. They are not quick fixes, but sustained practices that provide your body with the raw materials and conditions necessary for optimal function. By focusing on these core areas, you create a powerful foundation for hormonal balance, empowering your body’s innate intelligence to restore its own equilibrium.

Nutritional Architecture the Building Blocks of Hormones

Your endocrine system cannot create its essential messengers from nothing. It relies on a steady supply of specific nutrients. Every meal is an opportunity to provide the architectural components for hormonal production. Consuming adequate protein is a critical starting point.

Protein is broken down into amino acids, which are the fundamental building blocks for peptide hormones ∞ a class that includes insulin, which manages blood sugar, and growth hormone, which is vital for cellular repair. Research shows that a protein-rich meal helps regulate appetite by decreasing the hunger hormone ghrelin and stimulating hormones that promote feelings of fullness. This simple dietary focus helps stabilize the metabolic signals that govern energy balance.

Healthy fats are equally indispensable. Your body uses cholesterol and specific fatty acids to synthesize steroid hormones, including testosterone and estrogen. Including sources like avocados, nuts, seeds, and fatty fish provides these essential precursors. Omega-3 fatty acids, in particular, are known to help modulate inflammation, a key factor that can disrupt hormonal signaling.

Conversely, diets high in processed foods and refined sugars can create a state of metabolic chaos, leading to insulin resistance and placing a significant burden on the pancreas and adrenal glands. Reducing your intake of these items is a direct way to lower systemic inflammation and support stable hormone levels.

The Role of Physical Movement in Hormonal Dialogue

Regular physical activity acts as a potent modulator of the endocrine system. Exercise improves blood flow, which means hormones are transported more efficiently to their target cells. It also increases the sensitivity of hormone receptors. Think of this as turning up the volume on a radio receiver; the signal comes through more clearly, so the body doesn’t have to “shout” by overproducing hormones.

One of the most well-documented benefits of exercise is its ability to improve insulin sensitivity, helping to regulate blood sugar levels and reduce the risk of metabolic disorders. Both aerobic exercise and resistance training have been shown to have a positive impact. Physical activity also helps manage cortisol levels.

While intense exercise can temporarily raise cortisol, consistent, moderate activity helps to lower baseline levels of this stress hormone, promoting a more balanced state. This has profound effects on everything from sleep quality to mood regulation.

Your daily lifestyle choices provide the essential building blocks and operational instructions for your entire endocrine system.

Stress the Great Endocrine Disruptor

Chronic stress is one of the most significant challenges to modern endocrine health. The body’s stress response, orchestrated by the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, is designed for acute, short-term threats. When a stressful situation arises, the brain signals the adrenal glands to release cortisol and adrenaline.

These hormones trigger the “fight-or-flight” response, increasing heart rate, liberating stored glucose for energy, and sharpening focus. This is a brilliant survival mechanism. However, the relentless, low-grade stressors of modern life ∞ work deadlines, traffic, financial worries, constant digital stimulation ∞ can cause this system to become chronically activated.

A state of prolonged high cortisol can disrupt nearly every hormonal axis in the body. It can suppress thyroid function, interfere with the production of sex hormones like testosterone and estrogen, and contribute to insulin resistance.

Learning to manage stress through practices like mindfulness, meditation, deep breathing exercises, or simply spending time in nature is not an indulgence; it is a clinical necessity for maintaining endocrine balance. These techniques help to activate the parasympathetic nervous system, the body’s “rest-and-digest” state, which acts as a direct counterbalance to the stress response, allowing the endocrine system to return to a state of equilibrium.

This initial exploration reveals that supporting your endocrine system is a deeply personal process, rooted in the foundational principles of nutrition, movement, and stress management. By understanding the biological reasons behind these strategies, you move from simply following advice to making informed, empowered choices about your health. You begin to provide your body with the consistency and resources it needs to perform its complex and vital work, laying the groundwork for a more profound sense of well-being.

Intermediate

Understanding the foundational pillars of nutrition and lifestyle is the first step. The intermediate path requires a more granular look at the specific biochemical processes that govern hormonal health and the targeted strategies that can influence them.

This involves moving beyond general wellness advice to a more precise application of clinical science, recognizing that the endocrine system is a web of interconnected feedback loops. A change in one part of the system inevitably ripples through the others. Here, we transition from the “what” to the “how” ∞ how specific dietary components are metabolized, how different forms of exercise elicit distinct hormonal responses, and how the intricate relationship between the gut and the brain directly shapes our endocrine reality.

Nutritional Nuances and Metabolic Control

The conversation about nutrition must evolve from broad categories like “protein” and “fats” to a more sophisticated understanding of their specific roles. For instance, the type of fat consumed has a direct impact on cellular communication.

While omega-3 fatty acids, found in fatty fish, are precursors to anti-inflammatory signaling molecules, an overabundance of omega-6 fatty acids, common in processed vegetable oils and packaged foods, can promote an inflammatory state that disrupts hormone receptor function. It’s a matter of balance. A diet rich in whole-food sources of fat creates a more favorable biochemical environment for hormone synthesis and signaling.

Furthermore, the concept of blood sugar regulation extends beyond simply avoiding sugar. The glycemic impact of all carbohydrates matters. High-fiber foods, such as vegetables, legumes, and whole grains, slow the absorption of glucose into the bloodstream. This prevents the sharp spikes in insulin that, over time, can lead to insulin resistance ∞ a condition where cells become less responsive to insulin’s signals.

When cells are resistant, the pancreas must produce more and more insulin to manage blood glucose, creating a state of hyperinsulinemia that is linked to a cascade of hormonal issues, including polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) and an increased risk of metabolic disease. Therefore, structuring meals to include protein, healthy fats, and high-fiber carbohydrates is a clinical strategy to maintain insulin sensitivity and support overall metabolic health.

The Gut Endocrine Axis

One of the most significant areas of advancing research is the role of the gut microbiome as a virtual endocrine organ. The trillions of bacteria residing in your digestive tract are not passive inhabitants; they are active participants in your physiology. The gut microbiota communicates with the rest of the body through several pathways, directly influencing hormonal balance.

For example, certain species of gut bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) like butyrate from the fermentation of dietary fiber. These SCFAs act as signaling molecules that can influence the production of gut hormones like glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) and peptide YY (PYY), which play roles in appetite regulation and glucose metabolism.

The gut is also involved in the metabolism of hormones, particularly estrogen. An imbalanced gut microbiome can impact an enzyme called beta-glucuronidase, which affects the recirculation of estrogen in the body. This connection highlights how gut health is intrinsically linked to the balance of sex hormones. Supporting the microbiome through a diet rich in diverse plant fibers (prebiotics) and fermented foods (probiotics) is a direct strategy to support this crucial endocrine function.

The gut microbiome functions as an active endocrine organ, producing and regulating compounds that systematically influence your body’s hormonal balance.

Advanced Exercise Protocols for Hormonal Optimization

Different types of exercise trigger distinct hormonal responses, and this can be leveraged for specific goals. While moderate aerobic exercise is excellent for managing stress and improving insulin sensitivity, high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and resistance training can have more profound effects on anabolic hormones.

- High-Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) ∞ This involves short bursts of all-out effort followed by brief recovery periods. This type of training has been shown to be particularly effective at stimulating the release of human growth hormone (HGH), which is critical for cellular repair, muscle growth, and maintaining a healthy body composition. HIIT can also significantly improve insulin sensitivity in a time-efficient manner.

- Resistance Training ∞ Lifting weights creates microscopic tears in muscle fibers. The repair process triggers the release of hormones like testosterone and HGH to rebuild the muscle stronger. For men, this is a key stimulus for maintaining healthy testosterone levels. For women, the hormonal response to resistance training supports bone density and lean muscle mass, both of which are crucial, especially during the metabolic shifts of perimenopause and menopause.

The timing and intensity of exercise also matter. Overtraining, without adequate recovery, can lead to chronically elevated cortisol levels, which can suppress the very hormones you are trying to support. This creates a state of hormonal dysregulation that can manifest as fatigue, poor sleep, and a plateau in performance. Therefore, a well-designed exercise program balances periods of high intensity with adequate rest and recovery, creating a sustainable stimulus for positive hormonal adaptation.

Minimizing Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals

Endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are synthetic compounds found in many everyday products that can interfere with the body’s hormonal systems. They can mimic hormones, block them from binding to their receptors, or interfere with their production and metabolism. While it is impossible to avoid all EDCs, taking steps to reduce exposure is a key strategy for protecting endocrine health.

Key sources of EDCs include certain plastics (like BPA and phthalates), pesticides, and chemicals used in personal care products. Simple strategies to reduce your burden include:

- Filtering Drinking Water ∞ Using a high-quality water filter can reduce exposure to EDCs that may be present in tap water.

- Choosing Glass and Stainless Steel ∞ Opt for glass or stainless steel containers for food and beverages instead of plastic, especially when heating food, as heat can cause chemicals to leach from plastic.

- Selecting Cleaner Personal Care Products ∞ Choose products free from phthalates, parabens, and synthetic fragrances.

- Prioritizing Whole and Organic Foods ∞ Eating a diet based on whole, unprocessed foods reduces exposure to chemicals found in packaging and preservatives. When possible, choosing organic produce can limit intake of pesticides.

By adopting these more nuanced strategies, you move into a proactive partnership with your body. You are not just providing general support; you are making precise choices based on a deeper understanding of the biochemical conversations that dictate your health. This intermediate level of engagement is about fine-tuning the signals you send to your endocrine system, creating a more resilient and responsive internal environment.

| Strategy | Mechanism of Action | Primary Hormones Affected |

|---|---|---|

| Consume a High-Fiber Diet | Slows glucose absorption, provides substrate for SCFA production by gut bacteria. | Insulin, GLP-1, PYY |

| Incorporate Omega-3 Fatty Acids | Serve as precursors to anti-inflammatory molecules, support cell membrane health. | Cortisol, Insulin |

| Engage in Resistance Training | Stimulates muscle protein synthesis and repair processes. | Testosterone, Human Growth Hormone |

| Practice Stress Management | Activates the parasympathetic nervous system, counteracting the HPA axis. | Cortisol, DHEA |

| Reduce EDC Exposure | Minimizes interference with hormone synthesis, transport, and receptor binding. | Estrogen, Testosterone, Thyroid Hormones |

Academic

An academic exploration of endocrine support demands a shift in perspective from lifestyle interventions to the intricate molecular mechanisms that govern hormonal homeostasis. At this level, we examine the endocrine system not as a collection of glands, but as a highly integrated neuro-hormonal-immune network.

The strategies discussed are grounded in systems biology, considering the complex interplay between genetic predispositions, epigenetic modifications, and environmental inputs. We will focus specifically on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis as a central regulator of the body’s response to stress and its profound, cascading effects on metabolic and gonadal function. Understanding how to modulate this axis is a cornerstone of advanced endocrine management.

The HPA Axis a Master Regulator under Chronic Stress

The HPA axis is the central command system for the stress response. It begins in the hypothalamus, which releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) in response to a perceived threat. CRH signals the pituitary gland to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which in turn travels to the adrenal cortex and stimulates the synthesis and release of glucocorticoids, primarily cortisol.

This system is regulated by a negative feedback loop ∞ rising cortisol levels are detected by the hypothalamus and pituitary, which then downregulate the production of CRH and ACTH, respectively, to restore balance. This is a highly efficient system for managing acute stressors.

The problem in modern physiology arises from chronic activation. Persistent stressors ∞ be they psychological, inflammatory, or metabolic ∞ lead to a sustained demand for cortisol. Over time, this can lead to several maladaptive states. One is cortisol resistance, where cellular receptors for cortisol become desensitized.

The brain, sensing a lack of cortisol signaling, continues to drive the HPA axis, leading to high levels of circulating cortisol that are nonetheless ineffective at the cellular level. This state is associated with systemic inflammation, metabolic syndrome, and mood disorders. Another potential outcome is HPA axis exhaustion or “adrenal fatigue,” where the system’s capacity to produce adequate cortisol in response to a stressor becomes impaired, leading to symptoms of profound fatigue and an inability to cope with stress.

Nutraceutical Modulation of the HPA Axis

Certain nutritional compounds have been studied for their ability to modulate HPA axis activity. These are not replacements for foundational lifestyle strategies but can be considered as targeted biochemical interventions.

- Phosphatidylserine ∞ This phospholipid is a component of cell membranes and is found in high concentrations in the brain.

Research suggests that supplementation with phosphatidylserine can help blunt the ACTH and cortisol response to physical and psychological stress. It appears to work by supporting the negative feedback mechanism of the HPA axis, helping to restore its normal sensitivity.

- Adaptogenic Herbs ∞ Herbs like Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) and Rhodiola rosea have been classified as adaptogens for their ability to help the body adapt to stress.

Clinical studies suggest that Ashwagandha can significantly reduce serum cortisol levels in chronically stressed individuals. The proposed mechanism involves its ability to modulate signaling within the HPA axis, reducing the exaggerated stress response.

Rhodiola is thought to work by influencing the levels and activity of monoamines like serotonin and dopamine in the brain, which can have a secondary effect on HPA axis regulation.

- L-Theanine ∞ An amino acid found primarily in green tea, L-theanine is known for its ability to promote a state of relaxed alertness.

It can cross the blood-brain barrier and has been shown to increase alpha brain wave activity, which is associated with a state of calm. Mechanistically, it may help to dampen the sympathetic nervous system’s response to stress, thereby reducing the initial trigger for HPA axis activation.

Chronic stress can lead to a desensitization of cortisol receptors, creating a state of ineffective hormonal signaling despite high circulating levels.

The Interplay between the HPA and HPG Axes

The Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis governs reproductive function through the coordinated release of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), luteinizing hormone (LH), and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), which ultimately control the production of testosterone and estrogen. There is a direct and often antagonistic relationship between the HPA and HPG axes.

High levels of CRH and cortisol can suppress the release of GnRH from the hypothalamus. This is a biologically intelligent survival mechanism ∞ in times of extreme stress, reproductive function is deprioritized in favor of immediate survival. However, in the context of chronic stress, this suppression can lead to clinically significant hormonal imbalances.

In men, it can contribute to low testosterone. In women, it can manifest as menstrual irregularities or an exacerbation of menopausal symptoms. Therefore, any clinical protocol aimed at supporting gonadal hormones must also address HPA axis dysregulation. A strategy that focuses solely on hormone replacement without mitigating the root cause of HPA axis over-activation will be inherently limited in its efficacy.

Metabolic Endotoxemia and Systemic Inflammation

A modern understanding of endocrine health must include the concept of metabolic endotoxemia. This refers to a condition where lipopolysaccharides (LPS), components of the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria, leak from the gut into the bloodstream.

This “leaky gut” scenario can be triggered by a diet high in processed fats and sugars and low in fiber, which disrupts the integrity of the intestinal barrier. Once in circulation, LPS is a potent trigger for the innate immune system, leading to a state of low-grade, chronic inflammation.

This inflammation is itself a powerful stressor that activates the HPA axis. Furthermore, inflammatory cytokines can directly interfere with insulin receptor signaling, contributing to insulin resistance. This creates a vicious cycle ∞ poor diet leads to gut dysbiosis and leaky gut, which causes inflammation, which in turn drives HPA axis dysfunction and insulin resistance, further disrupting metabolic and hormonal health.

This systems-level view demonstrates that strategies to improve gut barrier function ∞ such as consuming a high-fiber, nutrient-dense diet and potentially using targeted probiotics ∞ are fundamental to managing systemic inflammation and, by extension, supporting endocrine function.

| Intervention | Biological Target | Primary Outcome | Supporting Evidence Level |

|---|---|---|---|

| Phosphatidylserine Supplementation | HPA Axis Feedback Loop | Blunts cortisol and ACTH response to stress. | Moderate |

| Ashwagandha (Withania somnifera) | HPA Axis Modulation | Reduces serum cortisol in chronically stressed individuals. | Moderate |

| High-Fiber, Prebiotic-Rich Diet | Gut Microbiome and Intestinal Barrier | Reduces metabolic endotoxemia and systemic inflammation. | High |

| Omega-3 Fatty Acid Supplementation | Inflammatory Pathways | Reduces production of pro-inflammatory eicosanoids. | High |

In conclusion, an academic approach to supporting the endocrine system requires a deep appreciation for the interconnectedness of the body’s regulatory systems. It moves beyond simple lifestyle advice to the application of specific biochemical and physiological principles.

By focusing on modulating the HPA axis, understanding its relationship with the HPG axis, and addressing the root causes of systemic inflammation like metabolic endotoxemia, it is possible to develop highly targeted and effective strategies. This level of analysis forms the scientific bedrock upon which personalized wellness protocols are built, allowing for a truly sophisticated and proactive approach to managing one’s own health.

How Can The Gut Microbiome Directly Influence Brain Chemistry And Mood? The gut microbiota produces a wide array of neuroactive compounds, including serotonin, dopamine, and GABA. These molecules can influence the brain through both the vagus nerve, which forms a direct physical link between the gut and the brain, and by entering the bloodstream.

Alterations in the composition of the gut microbiome have been linked to changes in mood and behavior, suggesting that supporting gut health through diet is a viable strategy for influencing neurological and psychological well-being. This gut-brain axis is a critical component of the holistic view of endocrine and overall health.

What Is The Clinical Rationale For Using Peptide Therapies? Peptide therapies, such as Sermorelin or Ipamorelin, are used to stimulate the body’s own production of growth hormone from the pituitary gland. Unlike direct administration of HGH, these peptides work by augmenting the natural pulsatile release of the hormone, which is thought to be a safer and more physiologically balanced approach.

They are used to address age-related decline in growth hormone levels, with potential benefits for body composition, sleep quality, and tissue repair. This approach aligns with a model of restoring the body’s innate function rather than simply replacing a deficient hormone.

How Does Testosterone Therapy In Women Differ From Men? Testosterone therapy in women uses much lower doses than in men, typically administered to restore levels to the normal physiological range for females. It is often prescribed for symptoms like low libido, fatigue, and brain fog, particularly during perimenopause and post-menopause.

The goal is to re-establish a healthy hormonal balance, often in conjunction with estrogen and progesterone therapy. In contrast, TRT in men is designed to address hypogonadism and bring testosterone levels from a deficient state back into the optimal male range. The protocols and target levels are fundamentally different, reflecting the distinct physiological roles of testosterone in men and women.

References

- Clarke, G. et al. “Minireview ∞ Gut Microbiota ∞ The Neglected Endocrine Organ.” Molecular Endocrinology, vol. 28, no. 8, 2014, pp. 1221-1238.

- Ranabir, Salam, and K. Reetu. “Stress and hormones.” Indian Journal of Endocrinology and Metabolism, vol. 15, no. 1, 2011, p. 18.

- Kraemer, William J. and Nicholas A. Ratamess. “Exercise and the Regulation of Endocrine Hormones.” Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise, vol. 37, no. 5, 2005, pp. 813-823.

- Diamanti-Kandarakis, E. et al. “Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals ∞ A Endocrine Society Scientific Statement.” Endocrine Reviews, vol. 30, no. 4, 2009, pp. 293-342.

- Hill, E.E. et al. “Exercise and circulating cortisol levels ∞ the intensity threshold effect.” Journal of Endocrinological Investigation, vol. 31, no. 7, 2008, pp. 587-91.

- Glaser, R. and J. K. Kiecolt-Glaser. “Stress-induced immune dysfunction ∞ implications for health.” Nature Reviews Immunology, vol. 5, no. 3, 2005, pp. 243-51.

- Kelly, G.S. “Nutritional and botanical interventions to assist with the adaptation to stress.” Alternative Medicine Review, vol. 4, no. 4, 1999, pp. 249-65.

- Stachowicz, M. and A. Lebiedzińska. “The effect of diet components on the gut microbiome.” Roczniki Państwowego Zakładu Higieny, vol. 67, no. 2, 2016.

- Heiman, M. L. and F. L. Greenway. “A healthy gut microbiome is a key to weight management.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings, vol. 91, no. 6, 2016, pp. 787-800.

- Patel, Shanti, and Hyun-Wook Kim. “The impact of the gut microbiota on the reproductive and metabolic endocrine system.” Journal of Menopausal Medicine, vol. 23, no. 2, 2017, p. 81.

Reflection

You have now journeyed through the foundational, intermediate, and academic layers of your endocrine system. You have seen how your daily feelings connect to complex biological systems, and how those systems can be supported through conscious, informed choices. This knowledge is a powerful tool.

It transforms the conversation from one of passive suffering to one of active participation. The path forward is not about achieving a state of perfect, static health, but about engaging in a continuous, dynamic dialogue with your own body. What is it telling you today?

What resources does it need to meet the demands of your life? This is a journey of self-study, of applying these principles to your unique context and observing the results. The ultimate goal is to cultivate a deep, intuitive understanding of your own physiology, empowering you to navigate your health with confidence and agency.

The information presented here is the map; your personal experience is the compass. The next step is yours to take, with the reassurance that you have the capacity to become the primary architect of your own well-being.