Fundamentals

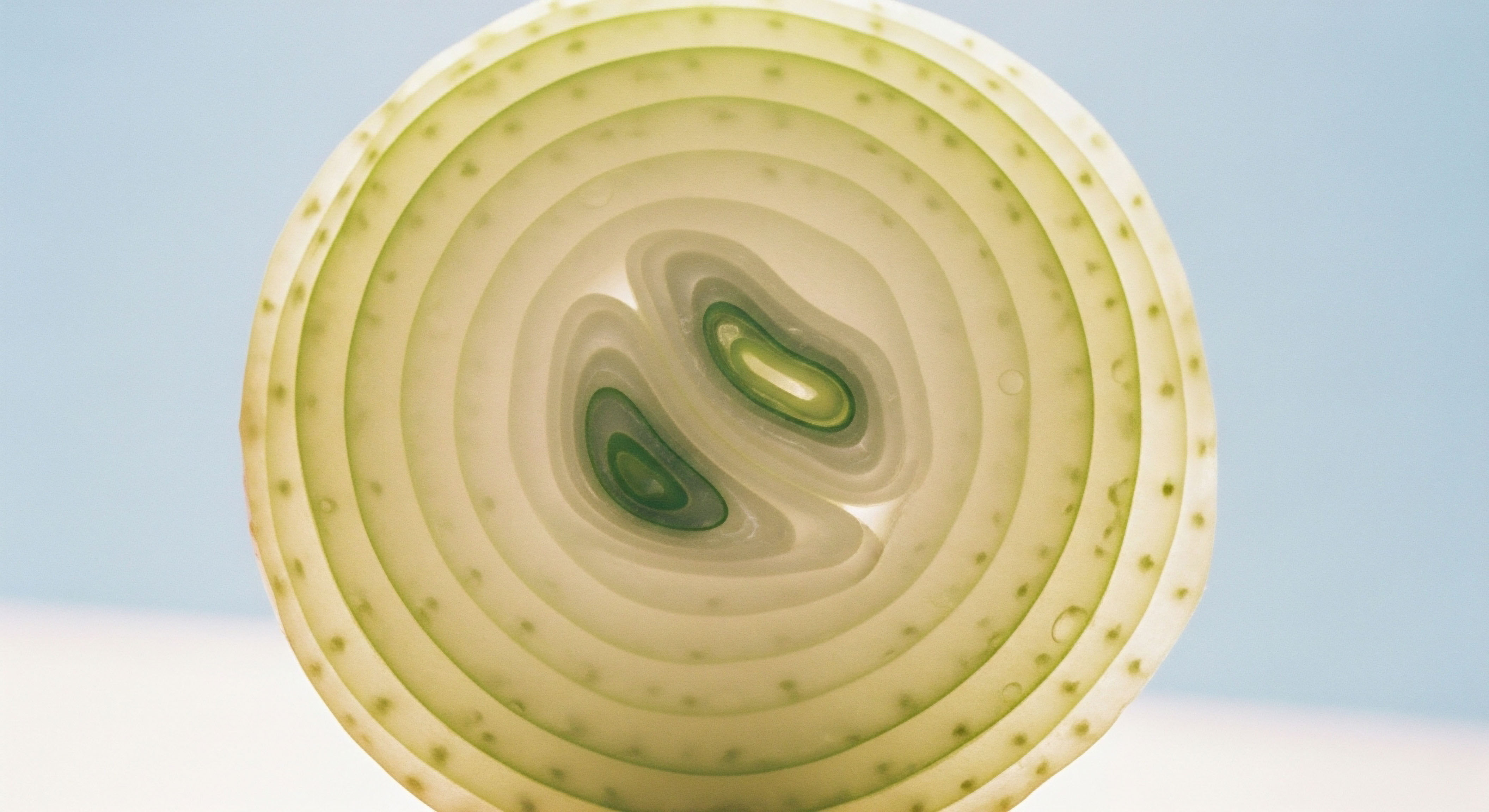

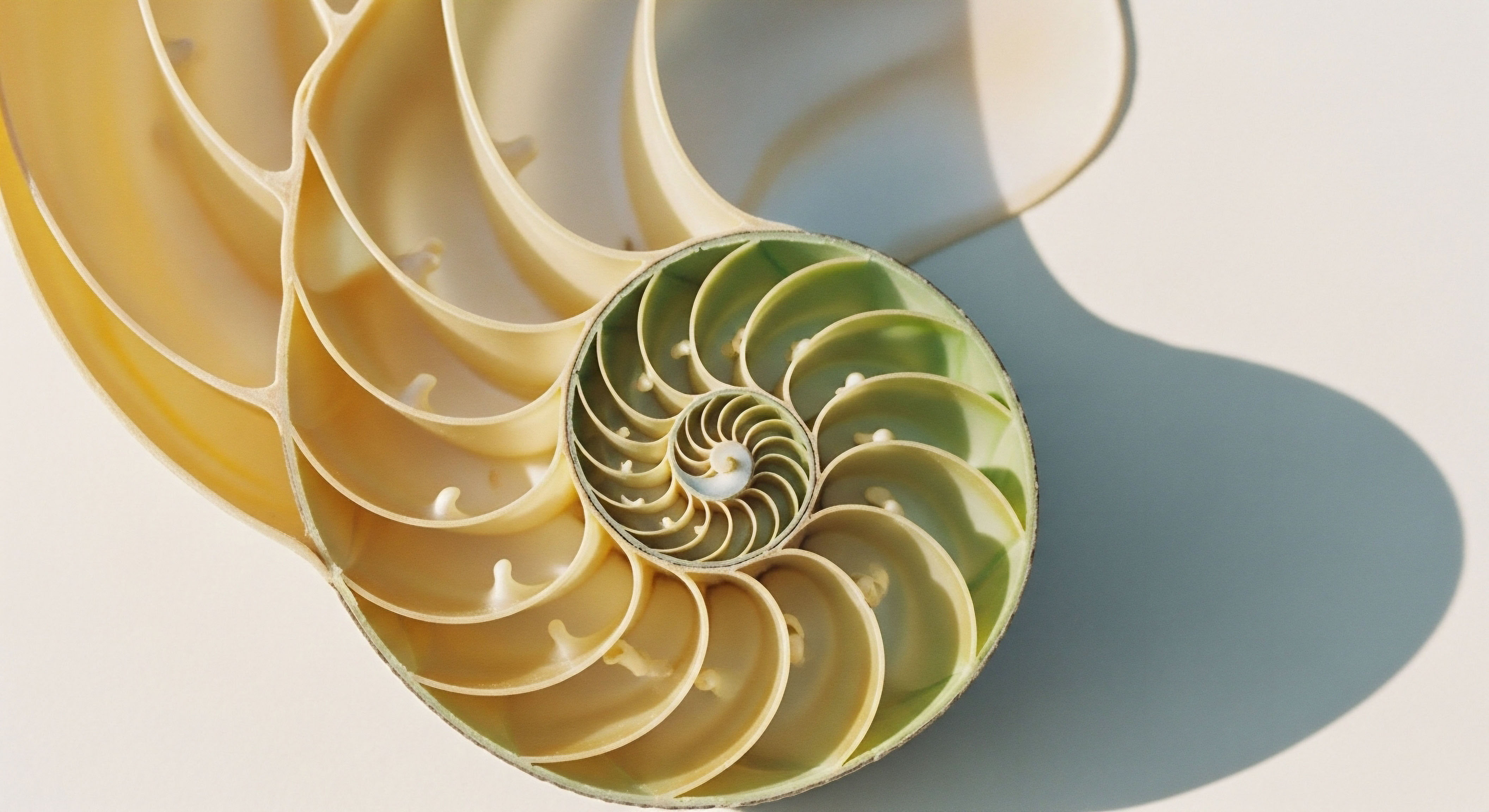

You meticulously track your cycle, your sleep, the subtle shifts in your energy throughout the month. This intimate chronicle of your body’s rhythms, a narrative written in data points, feels like a personal reclamation of your health. It is a modern form of self-awareness, a way to listen to the whispers of your own biology.

The question of who else might be listening, who else might be reading your story, is a profound one. It touches upon a deep-seated need for sovereignty over our own bodies and the information they produce.

The Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act, or HIPAA, is a familiar landmark in the landscape of health privacy, a law that safeguards the sanctity of your medical records within the clinical setting. Yet, the wellness apps Meaning ∞ Wellness applications are digital software programs designed to support individuals in monitoring, understanding, and managing various aspects of their physiological and psychological well-being. on your phone, the digital companions to your health journey, often exist outside of HIPAA’s protective embrace.

This realization can be unsettling, prompting a crucial inquiry ∞ what other safeguards stand in place to protect the deeply personal data you entrust to these applications?

The Intimate Language of Your Health Data

The data your wellness app Meaning ∞ A Wellness App is a software application designed for mobile devices, serving as a digital tool to support individuals in managing and optimizing various aspects of their physiological and psychological well-being. collects speaks a language of profound intimacy. It details the cadence of your heart, the quality of your sleep, the fluctuations of your hormones, and the geography of your daily life. This information, when woven together, creates a detailed portrait of your physiological and emotional landscape.

For those of us on a journey of hormonal optimization or metabolic recalibration, this data is particularly sensitive. It is the raw material of our personal science experiment, the evidence we use to understand our bodies and make informed decisions about our health.

The prospect of this data being handled without the utmost care and respect is a violation of the trust we place in these digital tools. It is a disruption of the sacred space we create when we choose to engage in the deeply personal work of understanding and nurturing our own biology.

The data from your wellness apps tells a story about you, a story that deserves to be protected.

Why HIPAA’s Shield Does Not Always Extend to Your Phone

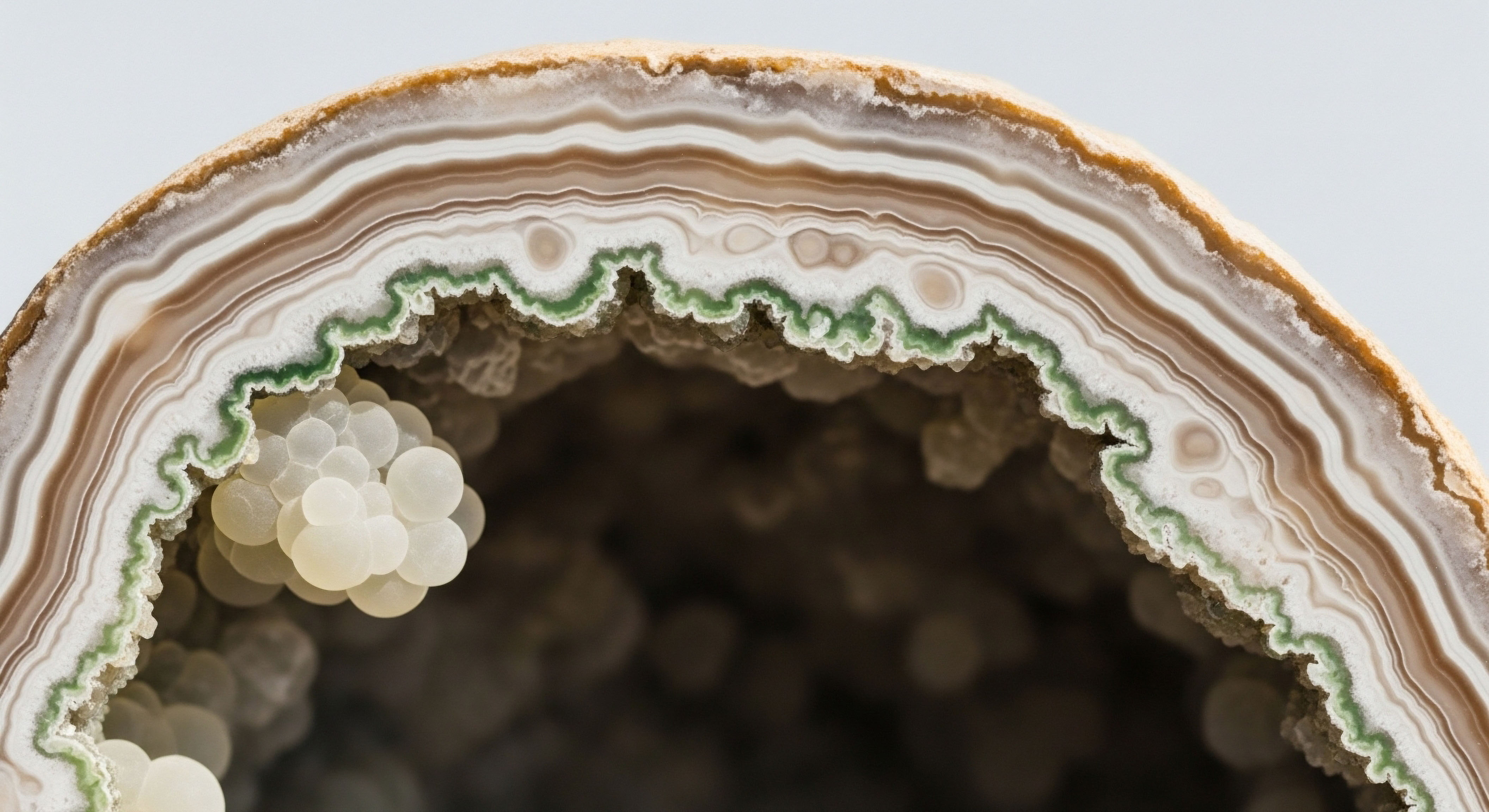

The architecture of HIPAA was designed for a different era of healthcare, one centered on the relationship between patients, providers, and insurers. The law’s protections apply to “covered entities” which are typically healthcare providers, health plans, and healthcare clearinghouses, and their “business associates”. Many wellness app developers do not fall into these categories.

They are technology companies that offer a service directly to you, the consumer. This distinction is a critical one. It means that the data you generate and share with these apps may not be subject to the same stringent privacy and security rules that govern your official medical records. This legal gap has created a new frontier in health privacy, one that we must navigate with awareness and intention.

The Federal Trade Commission Your Ally in the Digital Health Realm

In this evolving landscape, the Federal Trade Commission Counterfeit hormone trade poses severe legal penalties and significant commercial disruption, jeopardizing patient health through unverified, dangerous products. (FTC) emerges as a key guardian of consumer health data. The FTC is the nation’s primary consumer protection agency, tasked with preventing unfair, deceptive, and fraudulent business practices. Its authority extends to the digital marketplace, including the burgeoning world of wellness apps.

The FTC’s role is to ensure that companies are transparent about their data practices and that they honor the promises they make to consumers in their privacy policies. While the FTC’s powers are different from those of the Department of Health and Human Services (which enforces HIPAA), they provide an important layer of protection for your health data.

Two Federal Laws to Know beyond HIPAA

Two key federal legal frameworks, both enforced by the FTC, offer protection for your health data Meaning ∞ Health data refers to any information, collected from an individual, that pertains to their medical history, current physiological state, treatments received, and outcomes observed. in wellness apps. The first is Section 5 of the FTC Act, which prohibits unfair and deceptive trade practices. This law gives the FTC broad authority to take action against companies that mislead consumers about how their data is being used.

The second is the Health Breach Notification Rule Meaning ∞ The Health Breach Notification Rule is a regulatory mandate requiring vendors of personal health records and their associated third-party service providers to notify individuals, the Federal Trade Commission, and in some cases, the media, following a breach of unsecured protected health information. (HBNR), a more specific regulation that requires vendors of personal health records to notify consumers in the event of a data breach. Together, these two federal pillars provide a foundation for holding wellness app developers accountable for their data privacy and security practices. Understanding these laws is the first step toward becoming a more informed and empowered digital health consumer.

Intermediate

Navigating the legal terrain of health data privacy Meaning ∞ Health Data Privacy denotes the established principles and legal frameworks that govern the secure collection, storage, access, and sharing of an individual’s personal health information. beyond HIPAA requires a deeper understanding of the specific regulations that govern the digital wellness space. While the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) provides a crucial layer of oversight, its enforcement powers are channeled through specific legal instruments.

A thorough examination of these instruments, particularly the Health Breach Notification The FTC Health Breach Notification Rule requires non-HIPAA wellness apps to inform you if your personal health data is shared without your consent. Rule (HBNR) and Section 5 of the FTC Act, reveals both the strengths and limitations of federal protection for your personal health information. This knowledge empowers you to make more informed choices about the wellness apps you use and to better understand your rights as a digital health consumer.

A Closer Look at the Health Breach Notification Rule

The Health Breach Notification Rule Meaning ∞ The principle mandates informing individuals when their protected health information, particularly sensitive hormonal profiles or treatment plans, has been compromised. (HBNR) is a targeted regulation designed to fill a specific gap in health data privacy law. It applies to entities that are not covered by HIPAA, such as many direct-to-consumer wellness apps and online health services.

The rule’s primary function is to ensure transparency in the event of a data breach, mandating that affected individuals are promptly notified. This allows consumers to take steps to protect themselves from potential harm, such as identity theft or the unauthorized disclosure of sensitive health information.

Who the HBNR Protects

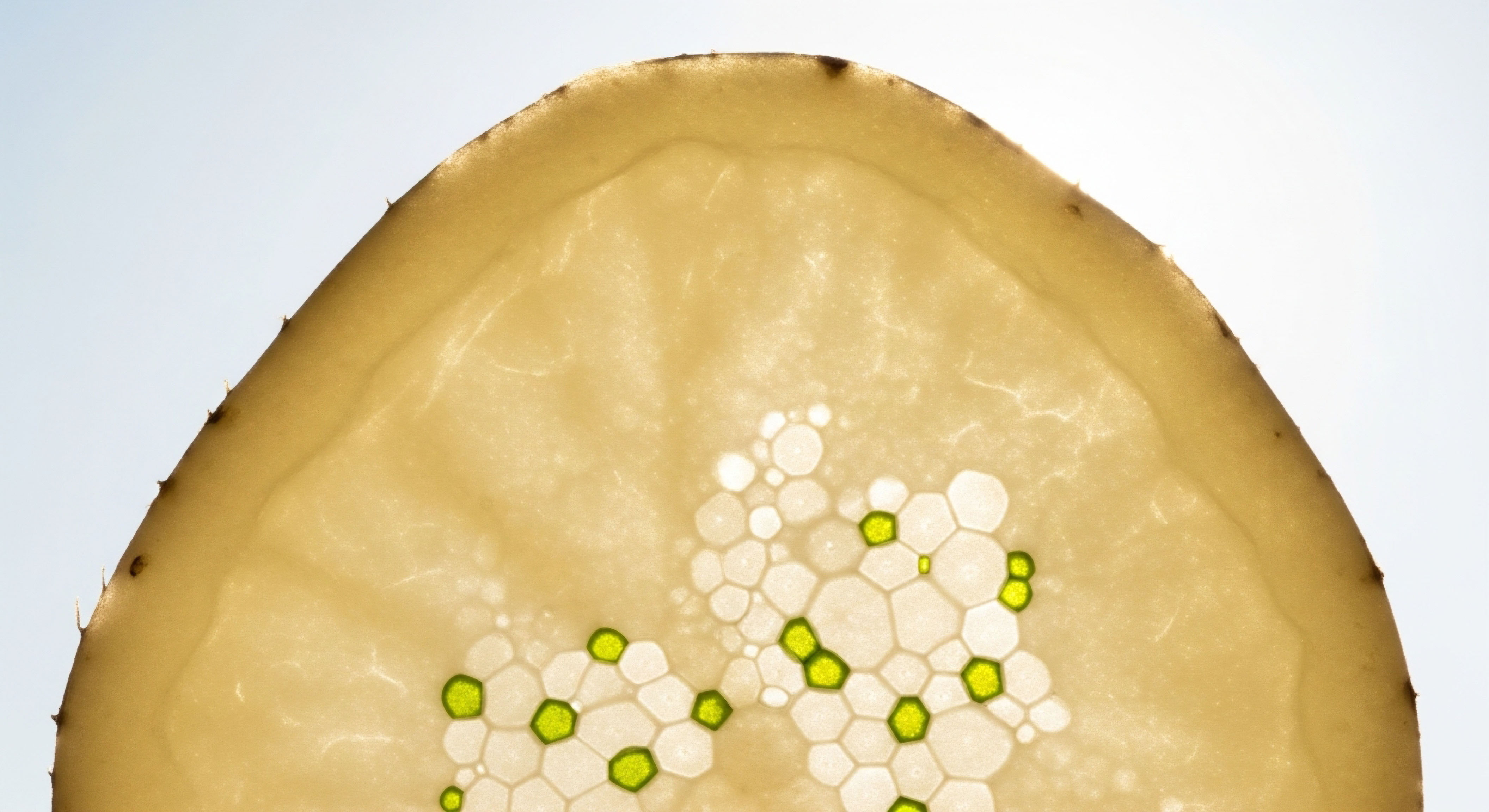

The HBNR applies to “vendors of personal health records” and “PHR-related entities.” A personal health record Meaning ∞ A Personal Health Record (PHR) is a secure, comprehensive compilation of an individual’s health information, directly managed by the person. (PHR) is defined as an electronic record of an individual’s identifiable health information that can be drawn from multiple sources and is managed, shared, and controlled primarily by or for the individual.

The FTC has interpreted “drawn from multiple sources” broadly, meaning that an app that collects information directly from you and also syncs with another device, like a fitness tracker, would likely be covered. This broad interpretation is intended to capture a wide range of wellness apps that collect and manage health data.

What Constitutes a Breach under the HBNR

A “breach of security” under the HBNR is not limited to a malicious cyberattack. It includes any unauthorized acquisition of unsecured PHR identifiable health information. The FTC has made it clear that “unauthorized acquisition” can include the sharing of health data with third parties without the user’s explicit consent.

This is a critical point, as it extends the concept of a breach beyond traditional security incidents to include privacy violations. The rule applies to “unsecured” information, which means data that is not protected by a specific technology or methodology, such as encryption.

Notification Requirements in the Event of a Breach

In the event of a breach, the HBNR requires vendors of personal health records A secure, interoperable Digital Health Record transforms TRT documentation from a source of travel anxiety into a seamless clinical passport. to notify each affected individual in writing within 60 days of discovering the breach. If the breach affects 500 or more people, the vendor must also notify the FTC and, in some cases, the media.

This public disclosure requirement is intended to create a strong incentive for companies to invest in robust data security practices. The notification must include a description of the breach, the types of information that were compromised, and the steps individuals can take to protect themselves.

| Number of Individuals Affected | Notification Requirements |

|---|---|

| Fewer than 500 | Notify each affected individual within 60 days of discovering the breach. |

| 500 or more | Notify each affected individual, the FTC, and potentially the media within 10 business days of discovering the breach. |

Section 5 of the FTC Act and Deceptive Practices

Section 5 of the FTC Act Meaning ∞ The Federal Trade Commission Act, enacted in 1914, is a foundational United States federal law primarily designed to prevent unfair methods of competition and unfair or deceptive acts or practices in commerce. is a cornerstone of consumer protection law in the United States. It prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce.” The FTC has used this broad authority to take enforcement action against wellness app developers that have engaged in misleading or harmful data practices.

A practice is considered “deceptive” if it involves a material misrepresentation or omission that is likely to mislead a reasonable consumer. A practice is “unfair” if it causes or is likely to cause substantial injury to consumers that is not reasonably avoidable and is not outweighed by countervailing benefits to consumers or to competition.

- Deceptive Practices ∞ This can include making false or misleading statements in a privacy policy, such as claiming that user data will not be shared with third parties when, in fact, it is. The FTC has taken action against companies for failing to live up to their privacy promises.

- Unfair Practices ∞ This can include collecting and sharing sensitive health data without a user’s knowledge or consent, or failing to implement reasonable security measures to protect that data. The FTC’s focus on unfair practices recognizes that some data practices can be harmful to consumers even if they are not explicitly deceptive.

The Evolving Legal Landscape and the Role of States

While the HBNR and Section 5 of the FTC Act provide important federal protections, they do not create a comprehensive privacy framework for health data in the same way that HIPAA does for the healthcare sector. Recognizing these gaps, several states have passed their own privacy laws that provide additional protections for consumer health data. These state laws are creating a complex patchwork of regulations that wellness app developers must navigate.

State laws are increasingly setting a higher bar for health data privacy, pushing the entire industry toward greater accountability.

For example, the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), as amended by the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), gives consumers the right to know what personal information is being collected about them, the right to have that information deleted, and the right to opt-out of the sale of their personal information.

More recently, Washington’s My Health My Data Act has established even more stringent protections for consumer health data, including a broad definition of what constitutes health data and a private right of action that allows individuals to sue companies for violations. These state-level initiatives are putting pressure on Congress to consider a federal privacy law that would provide a uniform standard of protection for all Americans.

Academic

The proliferation of wellness applications and wearable technologies has precipitated a paradigm shift in the generation and custodianship of health-related data. This phenomenon, often termed the “datafication” of health, presents a complex web of ethical, legal, and societal challenges that transcend the traditional confines of healthcare regulation.

A critical academic inquiry into the federal legal frameworks governing this domain reveals a regulatory apparatus struggling to keep pace with technological innovation. This analysis will explore the theoretical underpinnings of data privacy Meaning ∞ Data privacy in a clinical context refers to the controlled management and safeguarding of an individual’s sensitive health information, ensuring its confidentiality, integrity, and availability only to authorized personnel. in the context of consumer-generated health data, dissect the political economy of the wellness data ecosystem, and contemplate future models for data governance that prioritize individual autonomy and digital sovereignty.

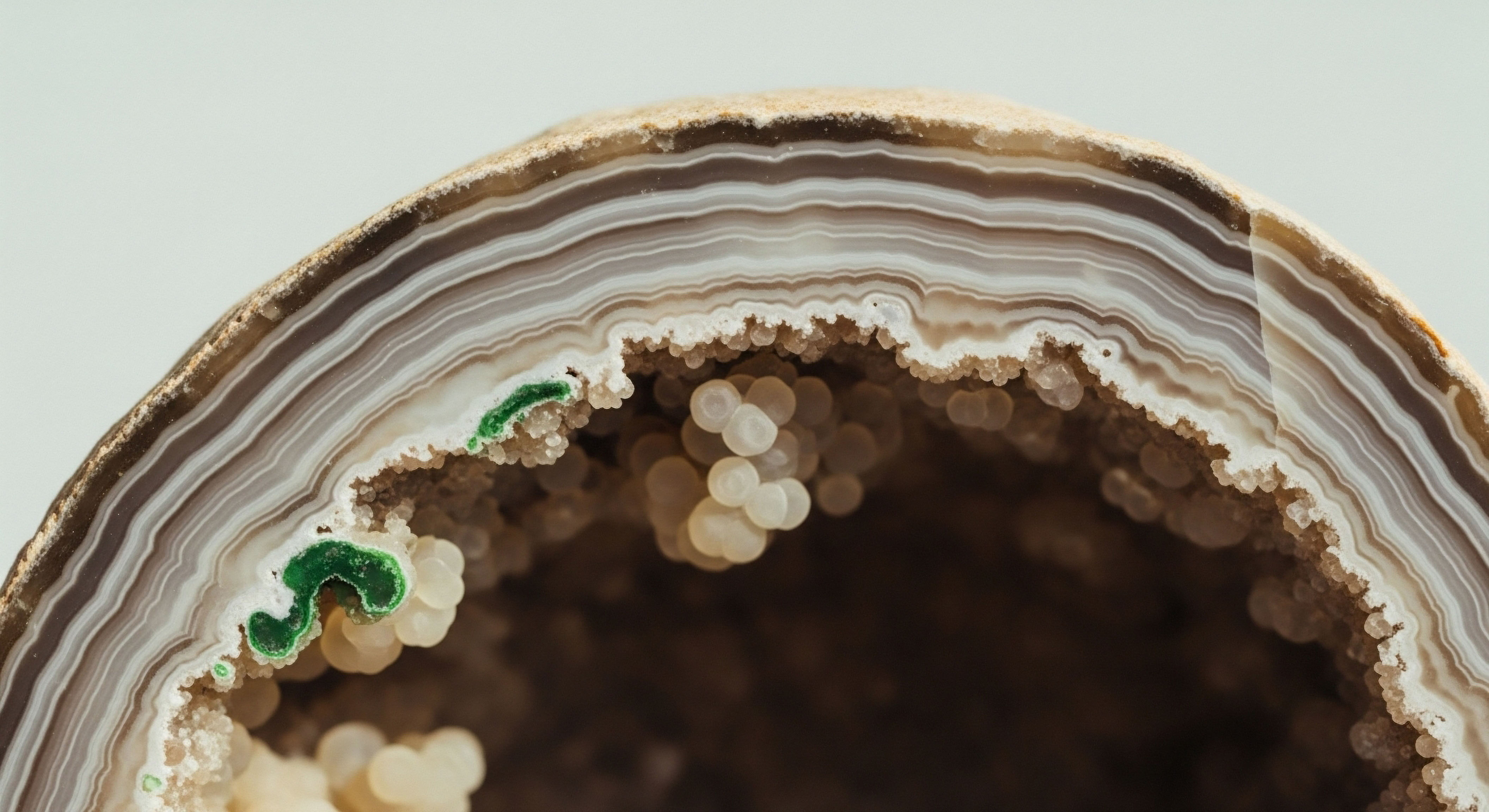

The Datafication of the Self and the Quantified Body

The act of tracking one’s own physiological and behavioral data, a practice known as “self-quantification,” has moved from the periphery to the mainstream. This trend is fueled by a desire for self-knowledge and a proactive approach to health management. However, the datafication of the self is a double-edged sword.

On one hand, it can empower individuals with unprecedented insights into their own biology, facilitating personalized interventions and a deeper connection to their bodies. On the other hand, it transforms the lived experience of health into a set of machine-readable data points, which can then be aggregated, analyzed, and monetized in ways that the individual may not fully comprehend or control.

Consent in the Age of Big Data a Legal Fiction?

The legal doctrine of consent, a cornerstone of data privacy law, is increasingly strained in the context of wellness apps. The long, dense, and often inscrutable privacy policies that accompany these apps present a form of “clickwrap” consent that is far removed from the ideal of a knowing and voluntary agreement.

The power asymmetry between the individual consumer and the technology company is vast, and the take-it-or-leave-it nature of these agreements leaves little room for negotiation. This raises fundamental questions about the meaningfulness of consent in the digital age and whether alternative legal frameworks are needed to protect individuals from the coercive pressures of the data economy.

The Political Economy of Wellness Data

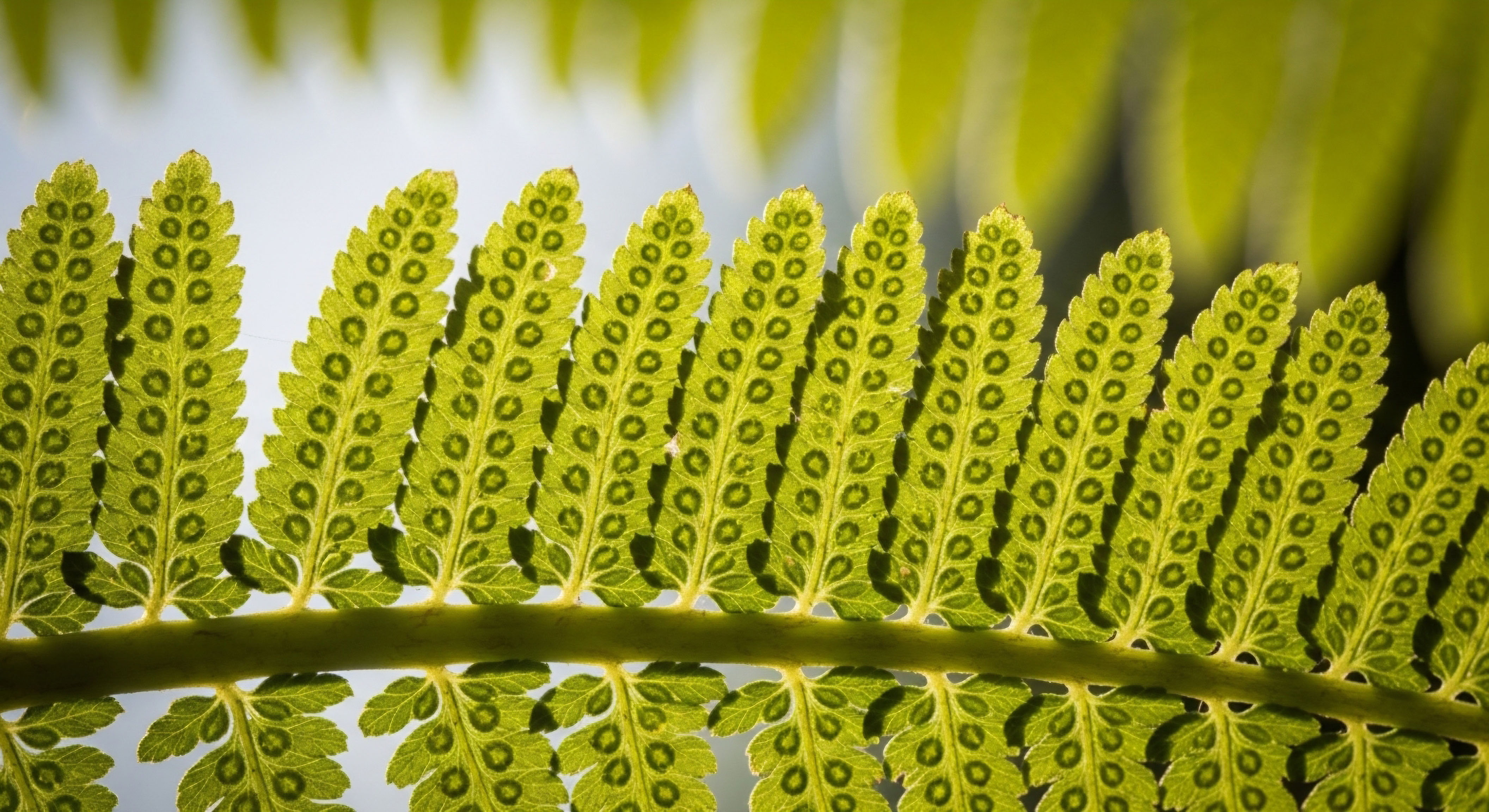

The data generated by wellness apps is a valuable commodity in the digital economy. It is used to train algorithms, develop new products and services, and, most lucratively, to target advertising. The business models of many wellness app companies are predicated on the collection and monetization of user data.

This creates a fundamental conflict of interest between the company’s profit motive and the user’s right to privacy. The flow of data from wellness apps to data brokers, advertising networks, and other third parties is often opaque, making it difficult for consumers to track where their data is going and how it is being used.

| Stage | Description | Key Actors |

|---|---|---|

| Data Generation | Individuals use wellness apps and wearable devices to track their health and fitness. | Consumers |

| Data Collection | Wellness app developers collect and store user data. | App Developers |

| Data Aggregation & Analysis | Data is aggregated and analyzed to identify trends and patterns. | App Developers, Data Brokers |

| Data Monetization | Data is sold to or shared with third parties for various purposes, including targeted advertising and market research. | Data Brokers, Advertisers, Insurance Companies |

Algorithmic Bias and the Perpetuation of Health Inequities

The algorithms that power wellness apps are not neutral. They are trained on vast datasets that may reflect and even amplify existing societal biases. For example, an algorithm trained primarily on data from a specific demographic group may be less accurate or effective for individuals from other groups.

This can lead to health recommendations that are inappropriate or even harmful for certain populations. The lack of transparency in how these algorithms are developed and validated makes it difficult to assess their fairness and to hold companies accountable for algorithmic bias. This is a critical issue for health equity, as it has the potential to widen existing disparities in health outcomes.

- Data Deserts ∞ Certain populations may be underrepresented in the datasets used to train wellness app algorithms, leading to a lack of accurate and relevant health information for these groups.

- Biased Recommendations ∞ Algorithms may provide biased or inappropriate health recommendations based on a user’s demographic characteristics, such as race, gender, or socioeconomic status.

- Reinforcing Stereotypes ∞ Wellness apps can reinforce harmful stereotypes about health and body image, particularly for women and marginalized groups.

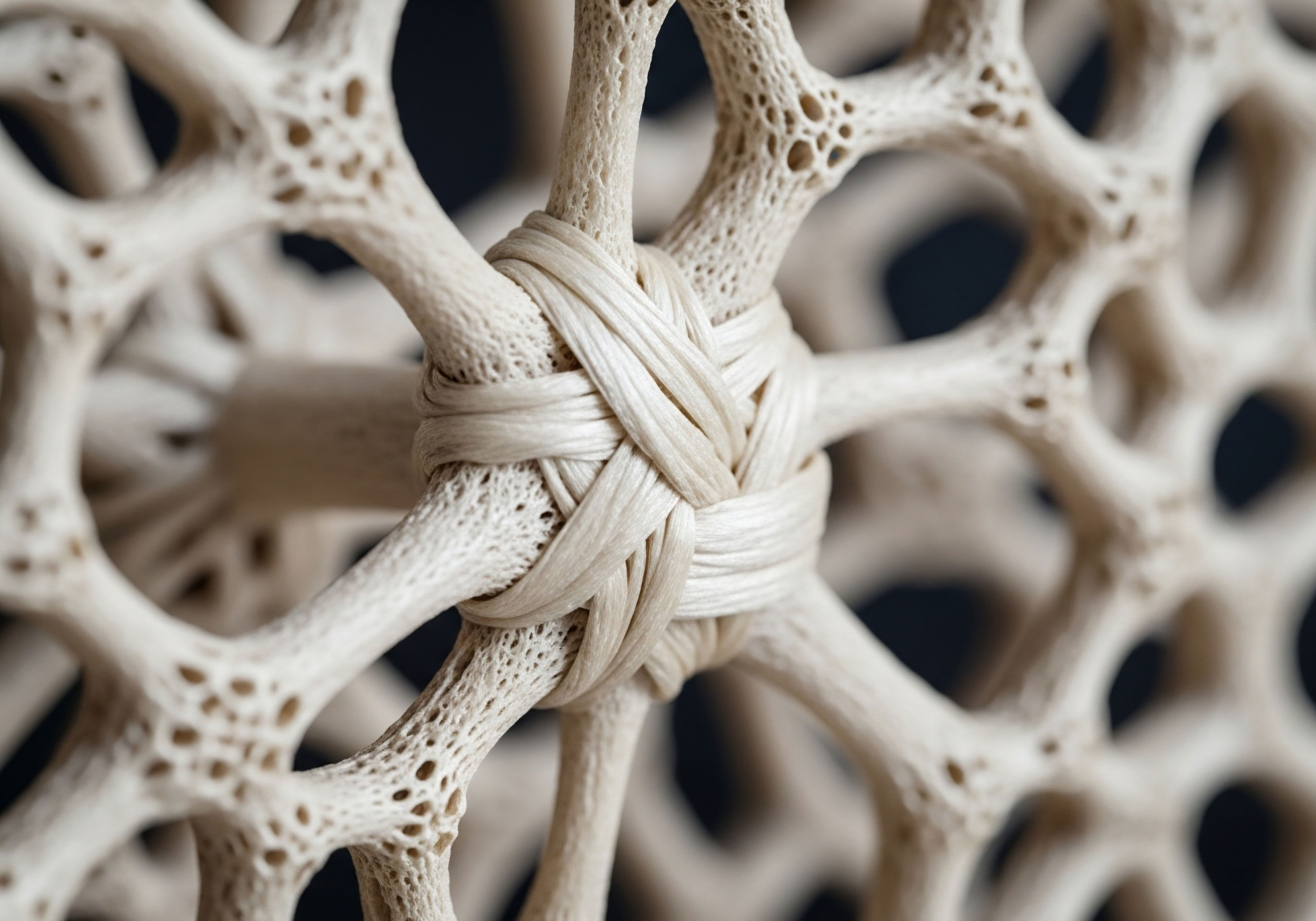

Toward a New Era of Digital Health Governance

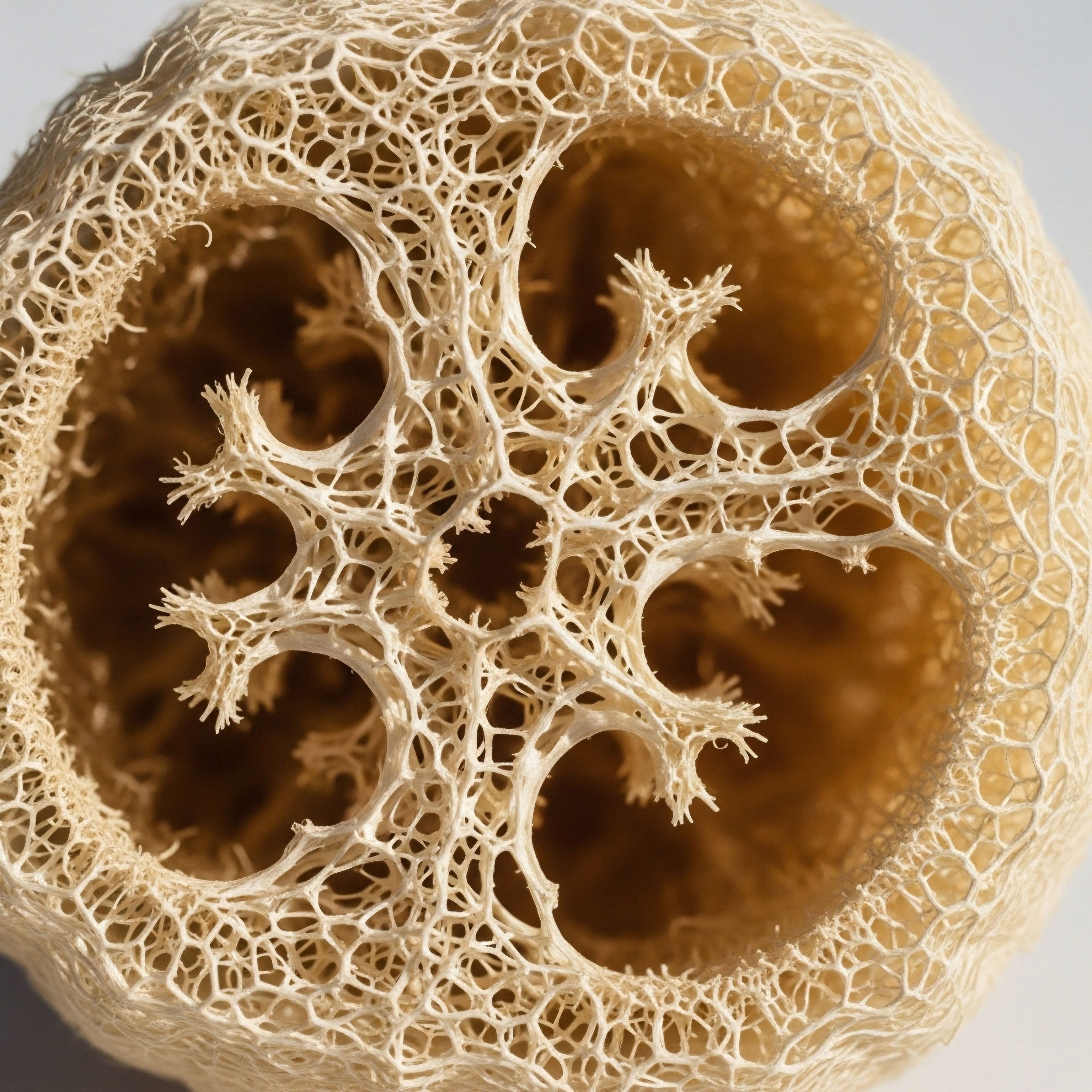

The challenges posed by the datafication of health require a new approach to data governance, one that moves beyond the limitations of the current legal framework. Several innovative models have been proposed to give individuals more control over their personal data.

These include personal data stores, which would allow individuals to store their data in a secure, centralized location and to grant access to third parties on a case-by-case basis. Another promising model is the data trust, in which a third-party organization would manage data on behalf of a group of individuals, with a fiduciary duty to act in their best interests.

The future of personalized wellness depends on our ability to build a data ecosystem that is grounded in trust, transparency, and respect for individual autonomy.

A more robust federal privacy law is also needed to establish a baseline of protection for all Americans. Such a law should include strong data minimization principles, purpose limitations, and a private right of action to empower individuals to enforce their privacy rights.

The development of a more ethical and transparent data ecosystem is not only a legal and technical challenge; it is a moral imperative. The future of personalized medicine and the promise of a more proactive and empowered approach to health depend on our ability to build a digital world that honors the sanctity of the individual and the profound intimacy of our biological selves.

References

- Federal Trade Commission. “Health Breach Notification Rule.” 16 C.F.R. pt. 318.

- Federal Trade Commission. “Section 5 of the FTC Act.” 15 U.S.C. § 45.

- Clark Hill PLC. “Beyond HIPAA ∞ How state laws are reshaping health data compliance.” Clark Hill, 26 June 2025.

- Wiley Rein LLP. “With Health Apps on the Rise, Consumer Privacy Remains a Central Priority.” Wiley, Feb. 2021.

- Holland & Knight LLP. “Important FTC Rules for Health Apps Outside of HIPAA.” Holland & Knight, 27 Sept. 2021.

- Ramirez, Edith, and Julie Brill. “Strengthening Protections for Sensitive Health Data ∞ The FTC’s Health Breach Notification Rule.” Federal Trade Commission, 2016.

- Vayena, Effy, et al. “The Emergence of Governance in the Digital Health Arena.” The Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, vol. 46, no. 1, 2018, pp. 38-48.

- Cohen, I. Glenn, and Michelle M. Mello. “HIPAA and the Limits of U.S. Health Information Privacy Law.” JAMA, vol. 320, no. 2, 2018, pp. 139-140.

- Zuboff, Shoshana. The Age of Surveillance Capitalism ∞ The Fight for a Human Future at the New Frontier of Power. PublicAffairs, 2019.

- Ebeling, Mary F. E. Healthcare and Big Data ∞ Digital Specters and Phantom Objects. Palgrave Macmillan, 2016.

Reflection

Your health journey is a deeply personal one, a continuous dialogue between you and your body. The tools you use to facilitate that dialogue, including the wellness apps on your phone, should honor the sanctity of that conversation.

As you move forward, consider the digital extension of your health journey with the same intentionality you apply to your physical and emotional well-being. The knowledge you have gained about the legal landscape of health data privacy is a powerful tool.

It is the first step toward reclaiming your digital sovereignty and ensuring that your biological narrative remains your own. What will you do with this knowledge? How will it shape your relationship with the digital tools you use to support your health? The answers to these questions are as unique as you are, and they will form the next chapter in your personal story of wellness.