Fundamentals

The effort you invest in your health should yield predictable results, yet the body’s response to those efforts can feel like a shifting landscape over time. This experience is a direct reflection of intricate, age-related recalibrations within your endocrine system.

The conversation about testosterone and aging often begins with an acknowledgment of its gradual decline, a process that can start as early as the mid-30s. Total testosterone may decrease by approximately 0.4% annually, with a more pronounced decline in the biologically active free testosterone at a rate of 1.3% per year.

This hormonal shift provides the essential context for understanding why the same lifestyle inputs ∞ rigorous exercise, precise nutrition, restorative sleep ∞ produce a different physiological output in a 50-year-old compared to a 25-year-old.

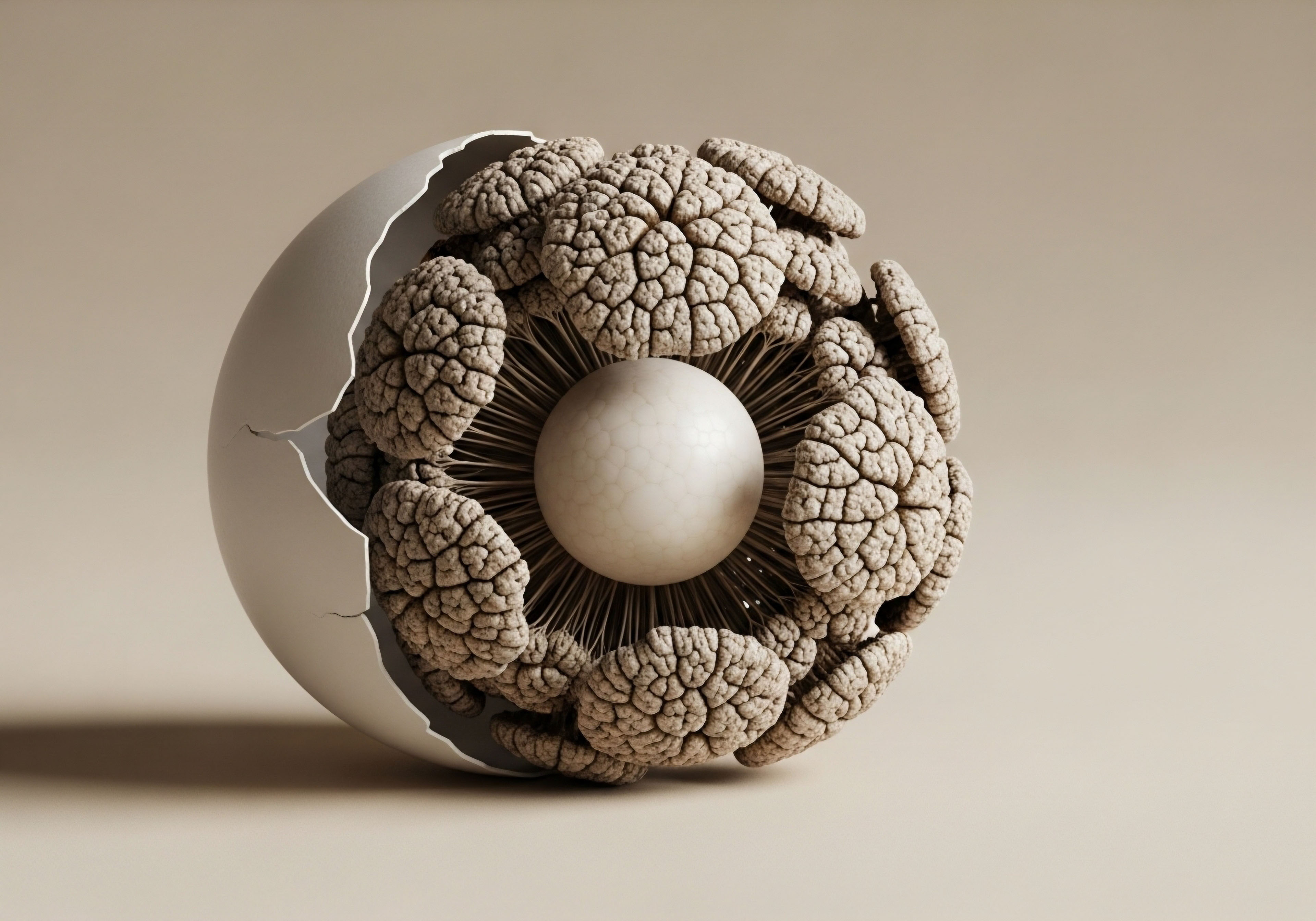

At the heart of this dynamic is the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Gonadal (HPG) axis, the sophisticated command-and-control system governing testosterone production. Think of it as a finely tuned internal thermostat. The hypothalamus releases Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH), signaling the pituitary gland to secrete Luteinizing Hormone (LH).

LH then travels to the Leydig cells in the testes, instructing them to produce testosterone. When testosterone levels are sufficient, they send a feedback signal to the hypothalamus and pituitary to down-regulate this process, maintaining equilibrium. Lifestyle interventions are powerful because they positively influence the signaling within this axis. For instance, high-intensity resistance training and adequate sleep enhance the pulsatile release of GnRH and LH, effectively turning up the thermostat’s set point.

The age-related decline in testosterone production creates a different physiological canvas upon which lifestyle changes exert their effects.

With advancing age, several components of this intricate system undergo subtle yet significant changes. The number and function of the testosterone-producing Leydig cells may decrease, and the sensitivity of the testes to LH signals can become attenuated. Furthermore, the brain’s own signaling can change, with studies in older men pointing to a reduction in GnRH outflow from the hypothalamus.

These physiological shifts mean that while the fundamental principles of lifestyle optimization remain constant, the magnitude of the hormonal response they elicit is inherently different. The body’s internal machinery for producing testosterone becomes less responsive, requiring a more deliberate and consistent application of positive lifestyle pressures to achieve and maintain optimal levels.

Intermediate

To appreciate the age-related variance in testosterone response, we must move beyond the systemic overview of the HPG axis and examine the cellular and molecular changes that define the aging endocrine environment. The diminished response to lifestyle interventions in older men is a direct consequence of physiological alterations at multiple levels of the testosterone production pathway. It is the interplay between central signaling, testicular function, and metabolic health that dictates the final hormonal output.

The Shifting Landscape of Testicular Function

The primary driver of age-related testosterone decline is a reduction in the functional capacity of the testes themselves. This involves two key age-dependent processes:

- Leydig Cell Decline ∞ These cells are the primary sites of testosterone synthesis. With age, there is a documented decrease in both the number and the functional efficiency of Leydig cells. This cellular senescence means that even with a strong LH signal from the pituitary, the testicular machinery’s maximum output is reduced.

- Altered LH Responsiveness ∞ The remaining Leydig cells may also exhibit a blunted response to Luteinizing Hormone. Imagine a factory where the workers are not only fewer in number but also less responsive to the manager’s instructions. The result is a diminished capacity to produce testosterone, even when the central command signals are robust.

How Does Metabolic Health Influence Hormonal Response?

Metabolic factors become increasingly intertwined with hormonal health as men age. The well-established inverse relationship between Body Mass Index (BMI) and testosterone levels persists and may even strengthen in significance after age 40. Excess adipose tissue is metabolically active, producing inflammatory cytokines and increasing the activity of the aromatase enzyme, which converts testosterone into estrogen. This process has profound implications for older men.

| Factor | Typical Change in Younger Men (20-35) | Typical Change in Older Men (50+) |

|---|---|---|

| HPG Axis Sensitivity |

Highly responsive to sleep, stress, and exercise, with robust feedback loops. |

Reduced GnRH pulsatility and attenuated LH response. |

| Leydig Cell Function |

Optimal number and function, high steroidogenic capacity. |

Decreased cell count and reduced efficiency per cell. |

| Aromatase Activity |

Generally lower, especially with lean body composition. |

Increases with age-associated gains in adiposity, converting more testosterone to estrogen. |

| Inflammation |

Lower baseline systemic inflammation. |

Higher levels of chronic, low-grade inflammation (“inflammaging”) can suppress testicular function. |

Lifestyle interventions such as diet and exercise aim to improve body composition, thereby reducing aromatase activity and inflammation. In a younger man, the hormonal axis responds swiftly to these improvements. In an older man, the response may be slower and less pronounced because the system is contending with a higher baseline of metabolic disruption and a less resilient production capacity.

Effective hormonal optimization in aging individuals requires addressing the systemic backdrop of metabolic health with the same rigor as direct hormonal signaling.

The Role of Lifestyle Interventions in an Aging System

Given this context, the goals of lifestyle changes adapt with age. While a younger man might use resistance training to maximize already robust testosterone production, an older man employs the same strategy for a different primary purpose ∞ to preserve existing function and improve the efficiency of a declining system.

Studies confirm that while physical activity and other factors are important, the correlation between age and declining free testosterone remains significant. This underscores that lifestyle choices become a crucial tool for mitigating an inevitable biological process, rather than simply augmenting a peak-performing system.

Academic

A sophisticated analysis of age-differentiated testosterone response necessitates a deep examination of the cellular mechanisms that underpin steroidogenesis and its age-related decline. The concept of “testicular senescence” provides a unifying framework, integrating mitochondrial dysfunction, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation as the core drivers of the attenuated response to lifestyle stimuli observed in older males. The clinical differences are manifestations of these profound cellular recalibrations.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction and Steroidogenic Decline

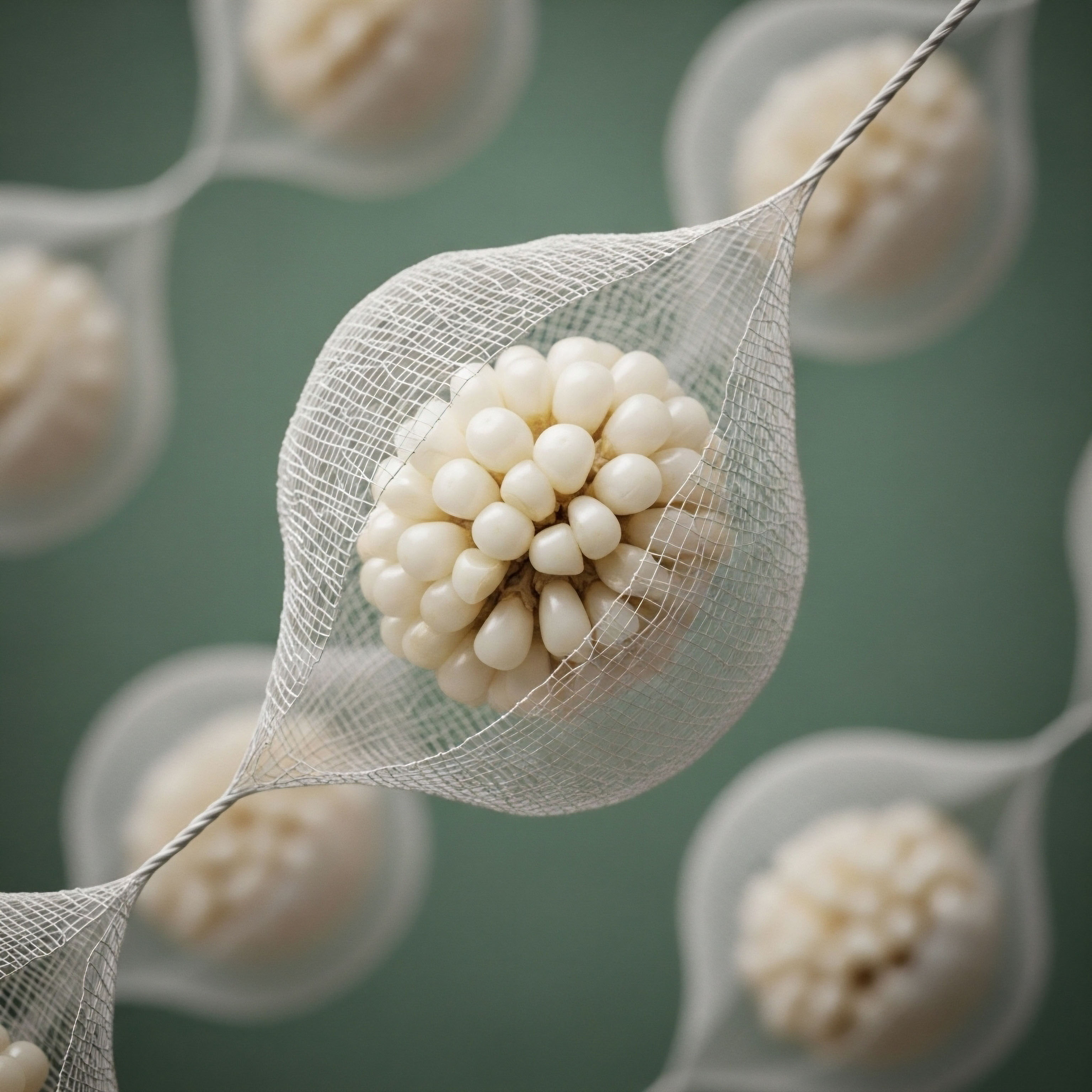

The synthesis of testosterone within Leydig cells is an energy-intensive process, critically dependent on healthy mitochondrial function. The very first step, the conversion of cholesterol to pregnenolone by the enzyme P450scc, occurs within the inner mitochondrial membrane. This is the rate-limiting step for all steroid hormone production.

Aging is intrinsically linked to a decline in mitochondrial efficiency, characterized by:

- Increased Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) Production ∞ As mitochondria age, the electron transport chain becomes less efficient, “leaking” more electrons that react with oxygen to form ROS. This creates a state of heightened oxidative stress within the Leydig cell.

- Reduced ATP Synthesis ∞ A decline in mitochondrial respiratory capacity leads to lower production of ATP, the energy currency required for the enzymatic conversions in the testosterone synthesis pathway.

- Impaired Mitochondrial Biogenesis ∞ The cellular processes for clearing damaged mitochondria (mitophagy) and generating new ones (biogenesis) become less effective, leading to an accumulation of dysfunctional organelles.

Lifestyle interventions like high-intensity interval training (HIIT) and resistance exercise are potent stimuli for mitochondrial biogenesis. In a younger individual, this stimulus falls on fertile ground, leading to a robust increase in mitochondrial density and function, thereby enhancing steroidogenic capacity.

In an older individual, the same stimulus faces the headwinds of accumulated mitochondrial damage and impaired repair pathways. The resulting improvement in testosterone production is therefore quantitatively smaller, as the intervention is simultaneously combating a deeper state of cellular decline.

What Is the Role of Inflammaging in Hormonal Suppression?

The age-associated increase in chronic, low-grade, systemic inflammation, termed “inflammaging,” is a key suppressor of the HPG axis. Pro-inflammatory cytokines, such as Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha (TNF-α), exert direct inhibitory effects on both the hypothalamus and the Leydig cells.

| Cytokine | Effect on Hypothalamus | Effect on Leydig Cells |

|---|---|---|

| IL-6 |

Can suppress GnRH secretion. |

Inhibits LH-stimulated testosterone synthesis. |

| TNF-α |

Disrupts normal GnRH pulsatility. |

Induces Leydig cell apoptosis and reduces steroidogenic enzyme expression. |

Lifestyle choices, particularly diet (e.g. consumption of anti-inflammatory omega-3 fatty acids) and exercise, are powerful modulators of this inflammatory state. In younger men, these interventions maintain an already low-inflammatory environment. In older men, these same interventions are tasked with actively suppressing a significantly elevated baseline of inflammaging.

Therefore, a substantial portion of the metabolic benefit from lifestyle changes in an older adult is directed toward quenching this inflammatory fire, with a consequently smaller portion available to directly up-regulate the HPG axis. The clinical result is a measurable, yet less dramatic, testosterone response compared to that of a younger counterpart whose system is not similarly burdened.

The diminished hormonal return on lifestyle investment with age is a direct reflection of the cellular energy deficit created by mitochondrial decay and inflammatory pressure.

This academic perspective reframes the question. The clinically significant difference in testosterone response is not a simple matter of age, but a reflection of the underlying cellular health of the individual. The chronological age serves as a proxy for the cumulative burden of oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage, and systemic inflammation that collectively blunt the body’s ability to respond to positive lifestyle stimuli.

References

- Mazur, Allan, et al. “Correlates of testosterone change as men age.” Aging Male, vol. 25, no. 1, 2022, pp. 63-72.

- Kühn, C. et al. “Relationship between testosterone serum levels and lifestyle in aging men.” The Aging Male, vol. 10, no. 4, 2007, pp. 183-189.

- National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Assessing the Need for Clinical Trials of Testosterone Replacement Therapy. Testosterone and Health Outcomes. National Academies Press (US), 2004.

- Camacho, E. M. et al. “Age-associated changes in hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular function in Middle-aged and older men are modified by weight change and lifestyle factors ∞ longitudinal results from the European Male Ageing Study.” The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, vol. 98, no. 5, 2013, pp. E840-E850.

- Wang, Yuxin, et al. “Age-related testosterone decline ∞ mechanisms and intervention strategies.” Reproductive Toxicology, vol. 114, 2023, pp. 109-119.

Reflection

Understanding the intricate biological shifts that accompany aging transforms the conversation from one of limitation to one of precision. The knowledge that your body’s internal environment is different now than it was decades ago is the foundational insight for a more intelligent and personalized approach to wellness.

Your lived experience of seeing diminished returns from familiar efforts is validated by the complex science of cellular senescence and endocrine recalibration. This awareness is the first, most critical step. It invites a shift in strategy, moving from broad efforts to targeted, sustainable protocols that respect the physiological realities of your current biology, empowering you to work with your body’s systems, not against them.