Fundamentals

Your question reaches into a profound truth about human vitality, one that touches upon the very architecture of how we, and especially our children, build a lasting relationship with well-being. From a clinical perspective that observes the body’s intricate systems, the answer is clear.

Non-financial incentives for children’s wellness programs are more broadly permitted because they align with the fundamental principles of sustainable, internally-driven health. This is a matter of both legal design and, more importantly, biological integrity. The systems that govern a child’s development, from their neurological wiring to their endocrine responses, are geared toward learning and adaptation based on internal cues of satisfaction and competence.

To understand this, we must first appreciate the two primary forces that drive behavior. One is the internal, self-generated drive known as intrinsic motivation. This is the inherent satisfaction a child feels when they master a new skill, the simple joy of running in a field, or the sense of accomplishment from learning to cook a healthy meal.

It is a powerful, self-sustaining force. The other driver is extrinsic motivation, which comes from the outside world. It is the sticker on a chart, the praise from a mentor, or the financial reward for achieving a goal. While these external signals have their place, their effect is profoundly different on the developing human system.

The Architecture of Motivation

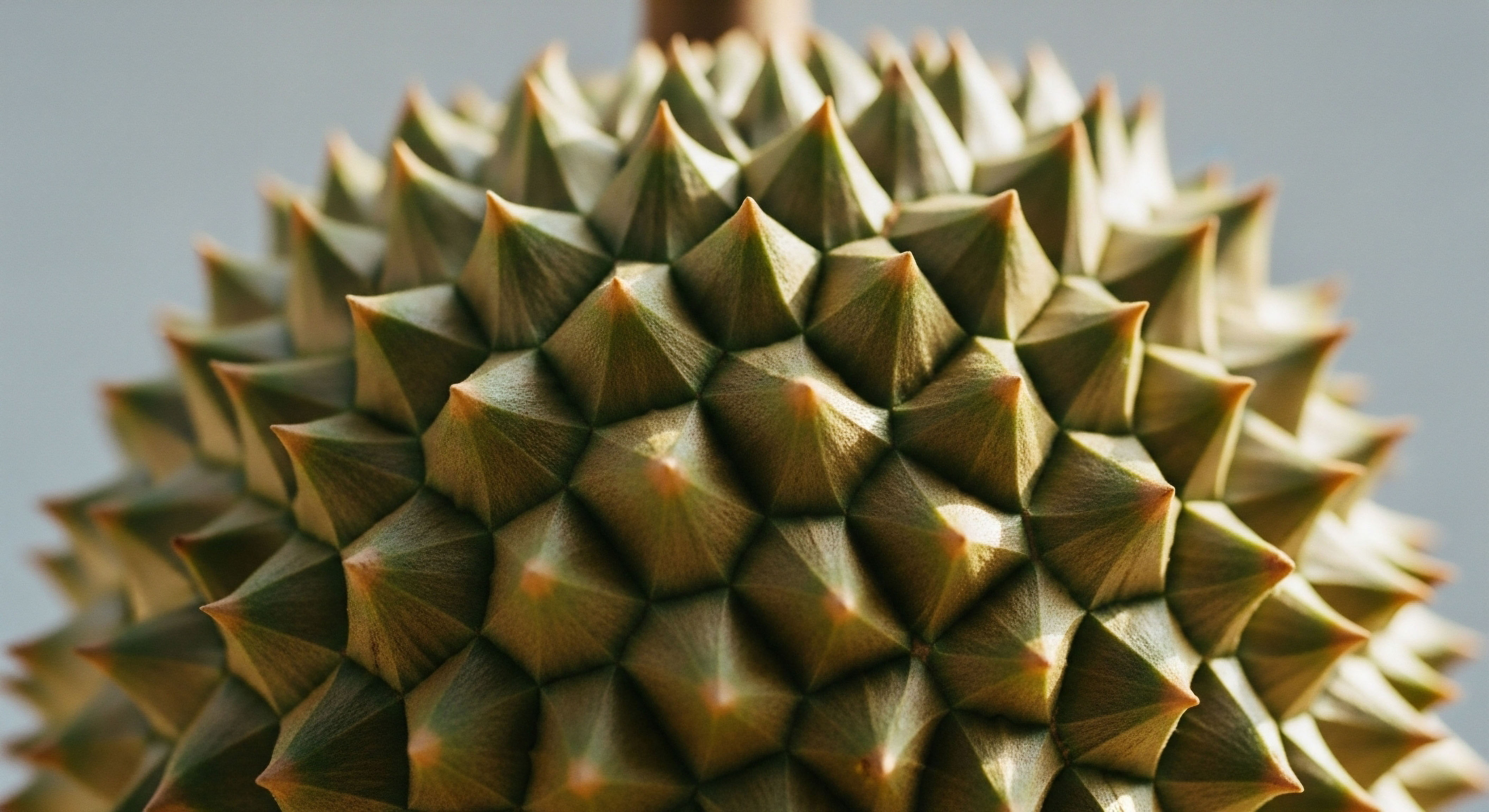

Think of a child’s motivation as a delicate ecosystem. Intrinsic motivation is the deep, nourishing soil that allows a love for healthy activities to grow naturally. It fosters curiosity, resilience, and a sense of personal ownership over one’s health.

A child who learns to enjoy the feeling of a strong body or the taste of fresh food is building a foundation for lifelong wellness. Their actions are rewarded by the very act of performing them, a closed, efficient loop within their own physiology.

Extrinsic incentives, particularly financial ones, function like a potent fertilizer. They can stimulate rapid growth and encourage a child to try something they otherwise would not. Yet, an over-reliance on this external input can alter the composition of the soil itself.

The activity is no longer performed for its inherent value, but for the separable outcome ∞ the reward. When the reward is removed, the motivation often disappears with it, leaving the soil less fertile than before. This is the core reason that regulatory frameworks are so cautious, especially where children are concerned. They are designed to protect that inner ecosystem of motivation, recognizing that true health cannot be perpetually purchased; it must be cultivated from within.

Why Are the Rules Different for Children?

A child’s neurological and endocrine systems are in a state of profound development. The pathways that govern reward, stress, and decision-making are highly malleable. Legal and ethical guidelines recognize this sensitivity. Regulations are stricter for children’s wellness programs because a child’s capacity for voluntary participation is different from an adult’s.

A significant financial incentive can feel less like an encouragement and more like a requirement to a child, a form of pressure that can inadvertently create a stressful association with the very health behaviors we seek to promote. Therefore, the permissibility of non-financial incentives stems from a deep-seated understanding, reflected in both law and clinical science, that the goal is to foster a love for well-being, not to create a transactional relationship with it.

Intermediate

Moving from the foundational ‘what’ to the clinical ‘why’ reveals a sophisticated interplay between legal statutes and psychological principles. The greater permissibility of non-financial incentives is not an arbitrary legal distinction; it is a direct reflection of a well-documented psychological phenomenon known as the “overjustification effect.” This principle explains how introducing a powerful external reward for an activity a child already finds enjoyable can paradoxically extinguish their internal drive to perform it.

The legal frameworks governing wellness programs, such as the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act (GINA), are structured to prevent this exact outcome.

The legal preference for non-financial incentives is a safeguard for a child’s developing sense of autonomy and internal motivation.

Under these regulations, wellness programs are broadly categorized into two types. ‘Participatory’ programs, which often use non-financial incentives like praise or small tokens, simply reward involvement and are lightly regulated. In contrast, ‘health-contingent’ programs, which tie significant financial rewards to achieving specific health outcomes, face strict limitations.

For adults, these incentives are capped, typically at 30% of the cost of health coverage, to ensure the program remains voluntary and not coercive. When it comes to children, the rules are even more stringent. GINA, for instance, explicitly prohibits offering incentives in exchange for a child’s health information, recognizing their vulnerability and the ethical imperative to protect their intrinsic motivation.

Comparing Incentive Structures

To clarify the operational differences, consider the distinct pathways through which these incentives function. Non-financial and participatory incentives are designed to support a child’s sense of competence and autonomy, which are the cornerstones of intrinsic motivation. Financial incentives, when tied to performance, risk shifting the locus of control from internal to external, transforming a wellness activity from a personal choice into a job.

| Incentive Type | Psychological Mechanism | Regulatory Scrutiny | Potential Long-Term Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Financial (e.g. Praise, Recognition) | Supports autonomy and competence; enhances intrinsic motivation. | Low; generally encouraged as part of participatory programs. | Sustainable, self-driven health behaviors; positive association with wellness activities. |

| Financial (Performance-Contingent) | Creates external locus of control; risks the overjustification effect. | High; strictly limited by HIPAA and prohibited for children’s data under GINA. | Behavior may cease when incentive is removed; potential for negative or stressful association with health goals. |

What Is the Role of Autonomy in Wellness?

The concept of autonomy is central to this discussion. True, lasting wellness is an expression of self-care, which must be volitional. When a child engages in a wellness activity because they want to, they are exercising autonomy. This internal decision-making process strengthens the neural pathways associated with self-efficacy and positive health identity. Non-financial incentives like verbal encouragement or allowing a child to choose their preferred physical activity serve to bolster this autonomy.

Conversely, a system of financial rewards can inadvertently undermine it. The decision-making process shifts from “I want to do this for myself” to “I must do this to get the reward.” This external pressure, however subtle, can erode the very foundation of self-determination that wellness programs should be building.

The law, in its wisdom, creates a space for programs that nurture this internal drive, making non-financial incentives the more broadly permitted and clinically sound approach for fostering a healthy future generation.

- Participatory Wellness Programs These initiatives focus on engagement over results. Examples include health education classes or participation in a team sport. Incentives here are generally non-financial or of low monetary value, and they are not contingent on achieving a specific biometric target.

- Health-Contingent Wellness Programs These programs are outcome-based. An individual must achieve a specific health goal, such as a target BMI or cholesterol level, to receive a reward. These are subject to much stricter legal controls due to their potential for coercion and discrimination.

- The Principle of Voluntarism A core tenet of wellness program regulation is that participation must be truly voluntary. An incentive cannot be so substantial that an individual feels they have no practical choice but to participate and disclose personal health information. This principle is applied with the utmost stringency in the context of children’s programs.

Academic

From a systems-biology perspective, the legal and psychological preference for non-financial incentives in children’s wellness is deeply congruent with the neurobiology of motivation and the development of the endocrine system. The distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic drivers is not merely a psychological construct; it is etched into the very function of our neural circuits.

When we analyze the physiological responses to different reward structures, the rationale for limiting externally contingent financial rewards becomes profoundly clear, especially during the sensitive developmental window of childhood and adolescence.

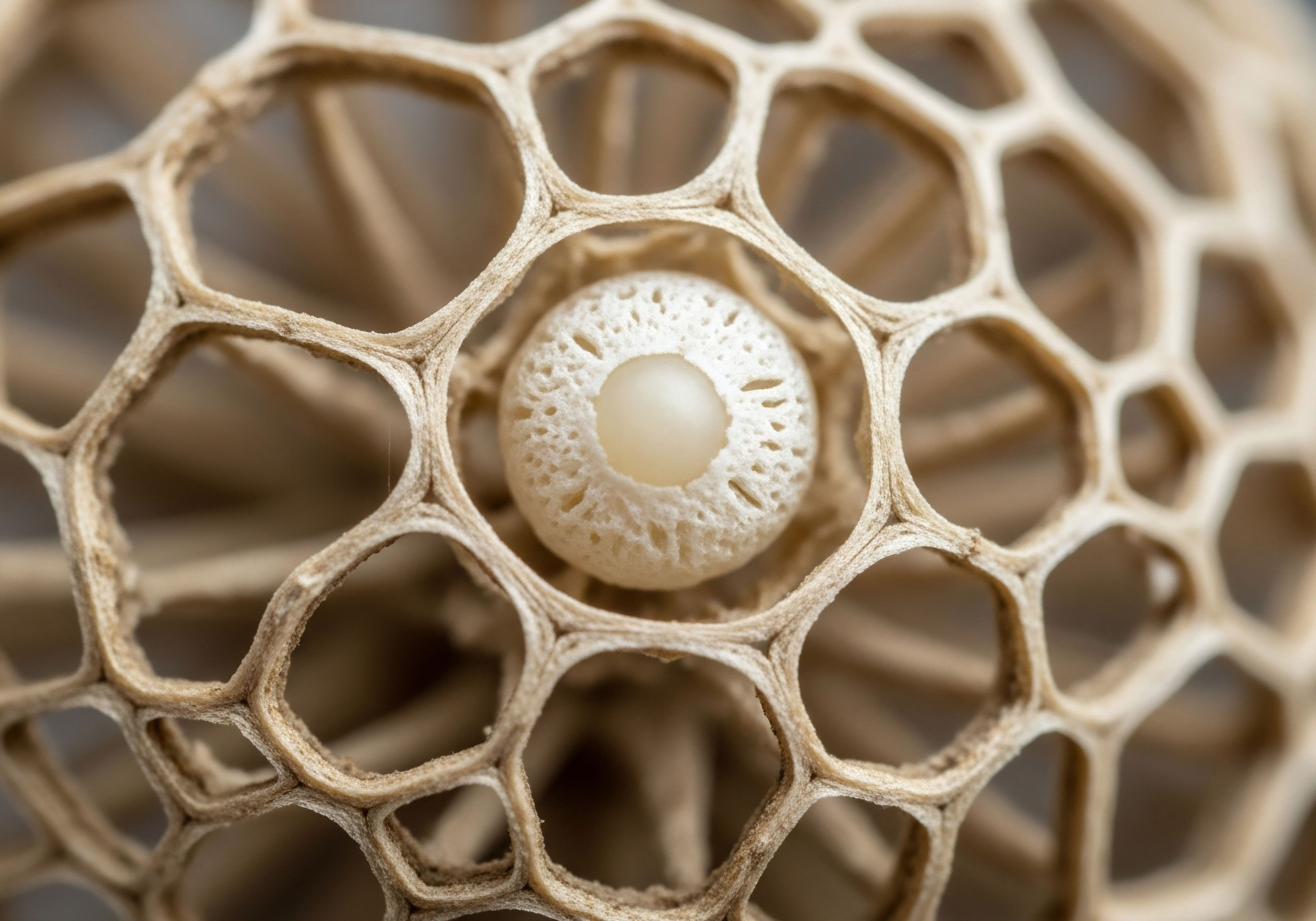

The architecture of the brain’s reward system reveals that internally generated satisfaction and externally provided rewards are processed through distinct, and sometimes competing, pathways.

Intrinsic motivation is heavily associated with activity in the anterior insular cortex. This region of the brain is critical for interoception ∞ the sensing of internal physiological states ∞ and the generation of subjective feelings. When a child engages in an activity for its inherent enjoyment, the insula integrates the sensory and cognitive inputs into a cohesive feeling of satisfaction.

This process is self-contained and self-reinforcing. In contrast, extrinsic motivation, particularly the calculation of effort versus a separable reward, engages different regions, such as the posterior cingulate cortex, which is involved in processing stored values and environmental contingencies.

Dopamine the Currency of Motivation

Both motivational pathways utilize the mesolimbic dopamine system; however, the nature of the dopaminergic signaling is critically different. Intrinsically motivated activities can lead to a sustained, tonic release of dopamine, creating a lasting sense of well-being and fulfillment that encourages repeated engagement. It is the neurobiological signature of finding an activity inherently valuable.

A performance-contingent financial incentive, conversely, tends to produce a phasic burst of dopamine upon anticipation and receipt of the reward. This powerful, short-lived signal can effectively “hijack” the valuation process. The brain learns to associate the dopamine release not with the health behavior itself, but with the external cue of the reward.

Research has shown that the introduction of such extrinsic reinforcers can dampen activity in the very brain regions associated with intrinsic motivation, providing a neural basis for the overjustification effect. The system’s focus shifts from the internal state of satisfaction to the external transactional gain.

How Does the Stress Axis Affect Motivation?

Furthermore, we must consider the role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, the body’s primary stress response system. A wellness program that applies significant pressure through high-stakes financial incentives can shift the physiological context of a health behavior from one of exploration and mastery to one of performance and potential failure.

This performance pressure can elevate levels of cortisol, the body’s main stress hormone. Chronically associating a health activity like exercise or nutritious eating with a cortisol-releasing stress response is deeply counterproductive. It can create a physiological aversion to the very behaviors the program aims to promote, undermining the goal of fostering lifelong wellness.

The table below outlines the divergent neuro-hormonal pathways, providing a clear biological rationale for the observed legal and psychological principles.

| Biological System | Response to Non-Financial/Intrinsic Incentives | Response to Financial/Extrinsic Incentives |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Brain Regions | Anterior Insular Cortex (interoception, subjective feeling). | Posterior Cingulate Cortex (valuation of external cues). |

| Dopamine Signaling | Sustained, tonic release associated with the activity itself, fostering long-term interest. | Phasic bursts tied to reward anticipation and receipt; can devalue the activity itself. |

| HPA Axis (Stress Response) | Generally neutral or down-regulating, associating wellness with calm and satisfaction. | Potential for activation and cortisol release due to performance pressure, creating a stress association. |

- Neuro-Hormonal Alignment The most effective wellness strategies are those that align with the body’s natural systems of reward and stress. Non-financial incentives that build competence and autonomy work with, not against, our innate neurobiology.

- Developmental Sensitivity The adolescent brain is characterized by heightened reward sensitivity and still-developing prefrontal cortex control. This makes it uniquely susceptible to the potent, short-term signaling of financial rewards, potentially creating dependencies that override the development of intrinsic motivation.

- Long-Term System Calibration The goal of any pediatric wellness initiative is to calibrate the individual’s internal systems toward a lifelong preference for healthy behaviors. This is achieved by creating positive, internally validated experiences, a process that is protected and favored by the legal limitations placed on purely transactional, financial incentives.

References

- Di Domenico, S. I. & Ryan, R. M. (2017). The Emerging Neuroscience of Intrinsic Motivation ∞ A New Frontier in Self-Determination Research. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 145.

- Fischer, C. Malycha, C. P. & Schafmann, E. (2019). The Influence of Intrinsic Motivation and Synergistic Extrinsic Motivators on Creativity and Innovation. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 137.

- Henderlong, J. & Lepper, M. R. (2002). The effects of praise on children’s intrinsic motivation ∞ a review and synthesis. Psychological Bulletin, 128 (5), 774 ∞ 795.

- Lee, W. & Reeve, J. (2013). Neural differences between intrinsic reasons for doing versus extrinsic reasons for doing ∞ an fMRI study. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 8 (4), 371 ∞ 379.

- Mello, M. M. & Rosenthal, M. B. (2008). Wellness programs and lifestyle discrimination–the legal limits. The New England journal of medicine, 359 (2), 192 ∞ 199.

- Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motivations ∞ Classic Definitions and New Directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25 (1), 54-67.

- U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. (2016). Final Rule on Employer Wellness Programs and the Genetic Information Nondiscrimination Act.

- U.S. Departments of Health and Human Services, Labor, and the Treasury. (2013). Incentives for Nondiscriminatory Wellness Programs in Group Health Plans; Final Rule. Federal Register, 78(106), 33158-33200.

Reflection

Calibrating Your Internal Compass

The knowledge that our legal systems and our biological frameworks are aligned on this subject offers a powerful insight. It suggests that the most effective path to wellness is one of authenticity. As you consider this information, the relevant question becomes personal.

Which activities, movements, or forms of nourishment bring a genuine sense of satisfaction to your system? Understanding the science of motivation is the first step. The next is to listen closely to the subtle, internal cues of your own biology, for this is where the blueprint for your unique and sustainable vitality resides.