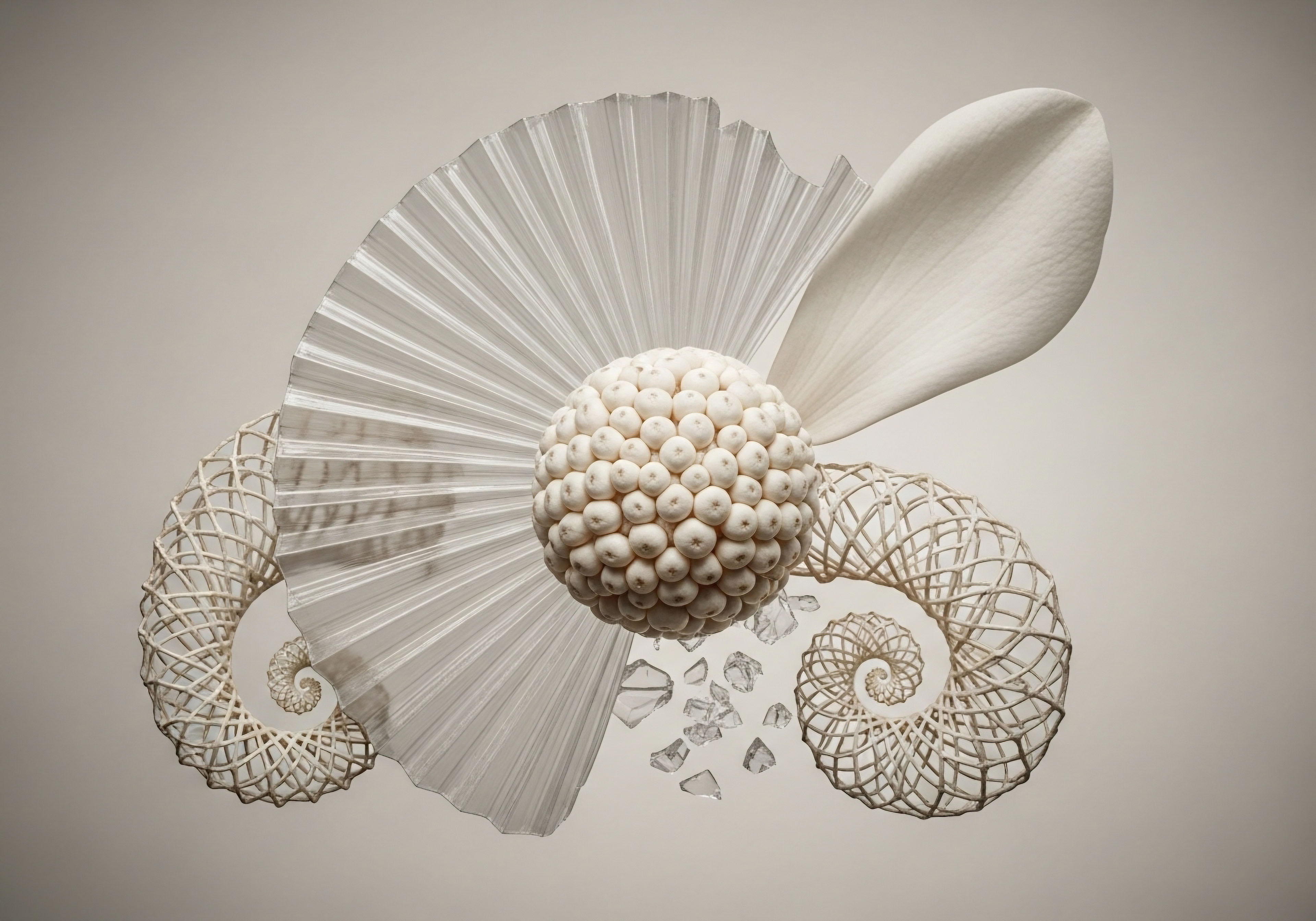

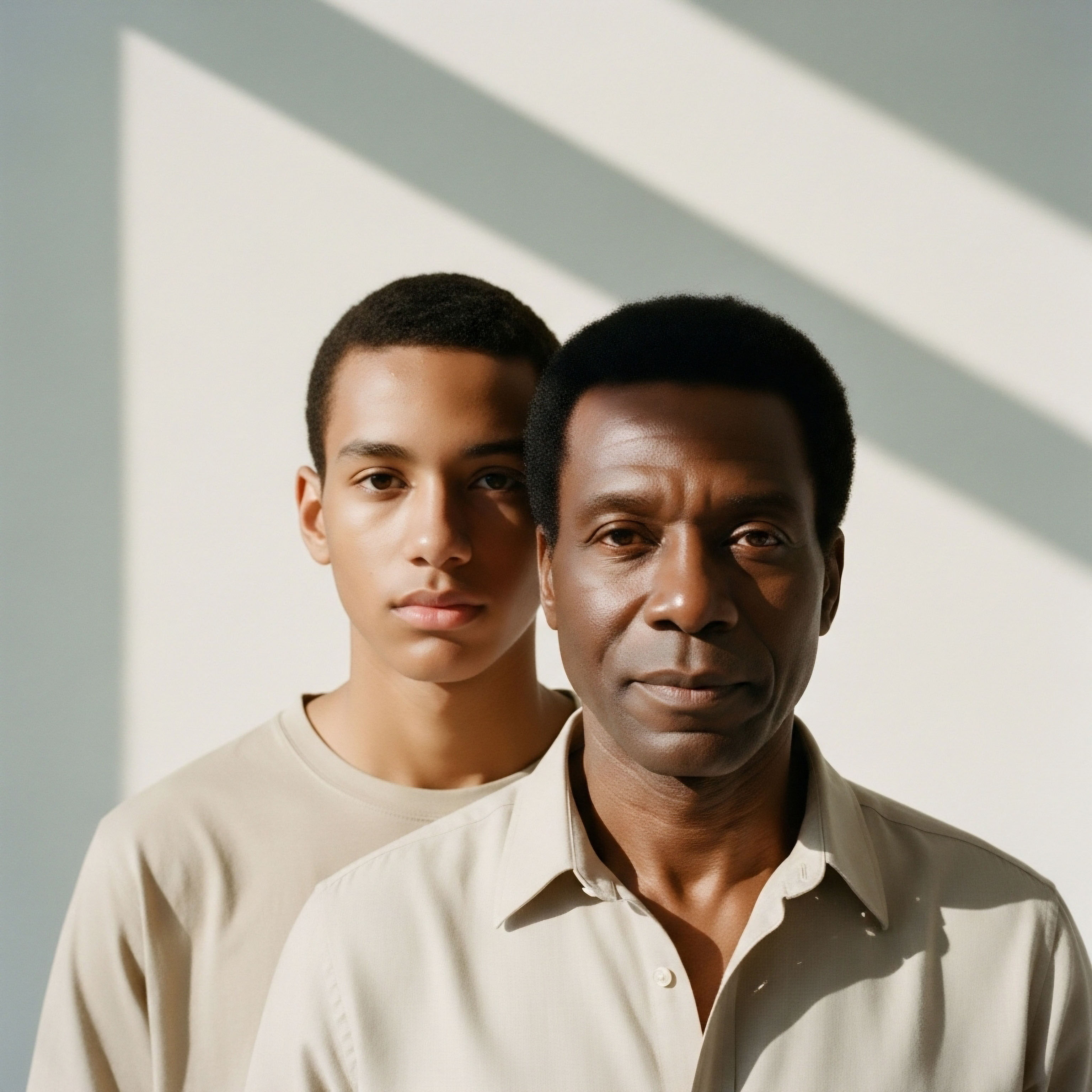

Optimal Hormonal Flow for Sustained Life Force

Unlock peak vitality and sustained life force through precise hormonal recalibration and advanced peptide signaling.

HRTioSeptember 26, 2025